Avoidant Attachment Style: Understanding Its Impact and Ways to Heal

Avoidant attachment develops early in life when caregivers are emotionally distant or unavailable. As adults, people with this attachment style often keep others at arm’s length to protect themselves from potential hurt. Understanding avoidant attachment is the first step toward developing healthier relationships and greater emotional wellbeing. The good news is that with awareness and practice, it’s possible to move toward a more secure attachment style.

1. Difficulty Forming Close Relationships

Beneath the surface of independence lies a genuine struggle to let others in. People with avoidant attachment often appear self-sufficient while maintaining emotional distance in relationships. They might feel uncomfortable with displays of affection or deep conversations about feelings.

This protective wall wasn’t built overnight. It developed as a childhood survival strategy when emotional needs weren’t consistently met. The brain learned that depending on others led to disappointment.

Recognizing this pattern is powerful. Many avoidant individuals don’t realize they’re keeping others at a distance until they notice repeated relationship patterns. Their partners often complain about emotional unavailability or feeling shut out during conflicts.

2. Emotional Suppression

“I’m fine” becomes the automatic response, even when storms rage within. Avoidant individuals often disconnect from their feelings as a self-protection mechanism. Years of practice make this emotional numbing seem normal and even necessary.

Physical symptoms sometimes reveal what words cannot. Unexplained headaches, stomach issues, or fatigue may signal buried emotions seeking expression. The body keeps score when feelings are pushed down.

The cost of this suppression is high. Research shows that chronically suppressed emotions can lead to health problems and relationship difficulties. When someone cannot access their authentic feelings, they miss important internal guidance about their needs and boundaries.

3. Fear of Dependence

“I can handle this myself” isn’t just a preference—it’s a deeply ingrained survival strategy. Those with avoidant attachment often experience intense discomfort when others offer help. Accepting assistance feels dangerous, as if surrendering control might lead to disappointment or abandonment.

Early experiences taught these individuals that self-reliance was safer than dependency. Perhaps caregivers were inconsistent, rejected their needs, or praised independence above all else. This created a core belief that needing others is a weakness.

Relationships become complicated when both partners cannot lean on each other. One-sided independence creates imbalance, preventing the mutual support that healthy relationships require. Breaking this pattern means recognizing that interdependence—not complete self-sufficiency—is actually a sign of strength.

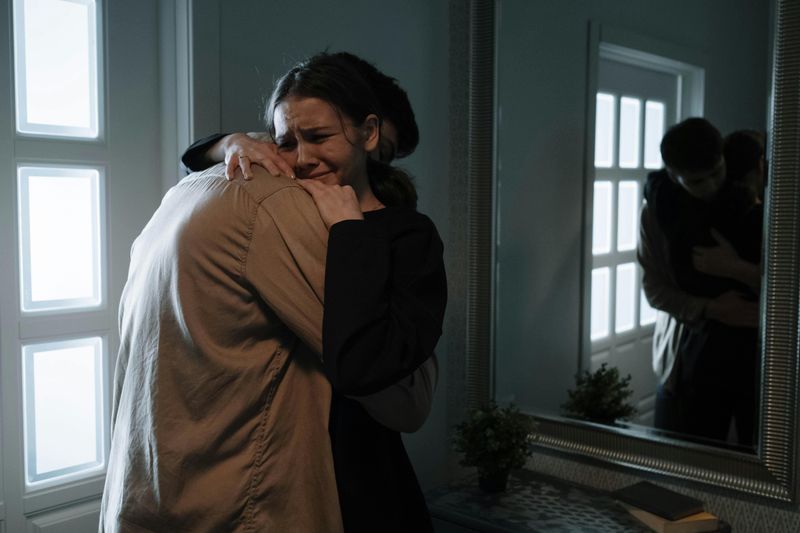

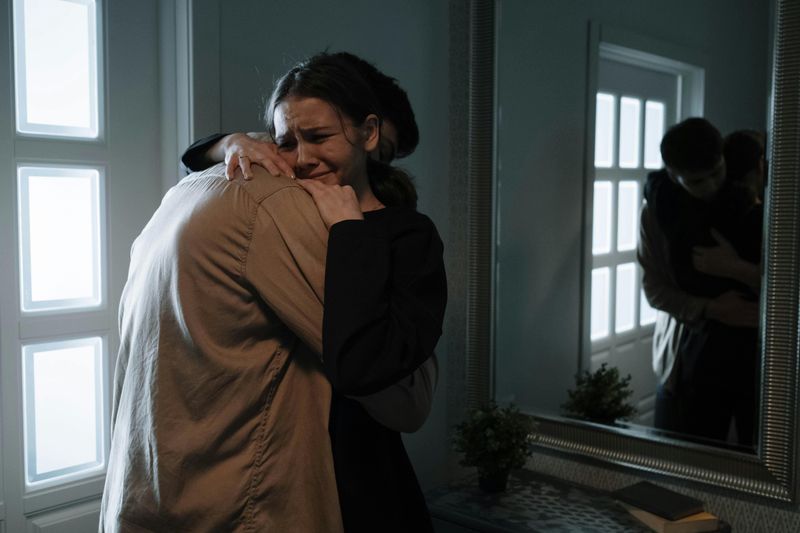

4. Relationship Instability

When conflict arises, the avoidant person’s first instinct is often retreat. This withdrawal isn’t about not caring—it’s about self-protection. The nervous system literally goes into flight mode, seeking emotional safety through distance.

Partners frequently misinterpret this behavior as rejection or lack of commitment. What looks like indifference may actually be overwhelm. The avoidant person might struggle to process emotions in real-time, especially during heated moments.

A telling pattern emerges in many avoidant relationships: the push-pull dynamic. When things get too close, the avoidant partner creates distance. When the distance grows too great, they reconnect—but cautiously. This creates a rollercoaster of connection and disconnection that leaves both partners feeling insecure about where they stand.

1. Therapeutic Support

Finding the right therapist creates a safe laboratory for exploring attachment patterns. Look for professionals specializing in attachment theory, trauma, or emotionally focused therapy. The therapeutic relationship itself becomes a powerful healing tool, as it provides a secure base for exploring vulnerability.

During therapy, childhood experiences are examined without judgment. Many avoidant individuals discover that their detachment developed for good reason—it protected them when emotional connection wasn’t safe. Understanding this compassionately reduces shame.

Progress happens in small steps. A skilled therapist won’t push for emotional exposure too quickly, respecting that avoidant patterns served a purpose. Instead, they help build internal resources and coping skills first, creating the safety needed for deeper work.

2. Building Emotional Awareness

Emotions provide valuable information, yet avoidant individuals often bypass this internal guidance system. Simple daily check-ins can begin rebuilding this connection. Try pausing three times daily to ask: “What am I feeling right now in my body and heart?”

Journaling offers a private space to explore emotions without immediate vulnerability to others. Start with physical sensations—tightness in the chest, shallow breathing, clenched jaw—and work backward to identify the feelings causing these reactions. Name the emotion without judging it.

Mindfulness practices strengthen the ability to stay present with uncomfortable feelings without escaping. Even one minute of focused breathing while acknowledging emotions builds tolerance. Remember that emotional awareness isn’t about fixing feelings—it’s about witnessing them with compassion.

3. Gradual Exposure to Vulnerability

Starting small creates sustainable change. Rather than diving into deep emotional waters, begin with shallow-end vulnerability. Share a minor preference or simple feeling with someone trustworthy: “I really enjoyed that movie” or “I felt disappointed when plans changed.”

Notice what happens in your body during these moments. Does your throat tighten? Does your mind race with regret after sharing? These physical responses are normal for avoidant individuals beginning vulnerability practice. They typically lessen with repeated exposure.

Create a vulnerability ladder with steps of increasing emotional risk. Perhaps sharing a childhood memory comes before revealing a current insecurity. Move up one rung only when the previous level feels manageable. Celebrate each step—even seemingly small acts of openness represent significant courage for someone with avoidant attachment.

4. Developing Secure Relationship Skills

Clear communication forms the foundation of secure attachment. Practice phrases that feel uncomfortable but build connection: “I need some time alone, but I still care about you” instead of simply disappearing. This honors both your need for space and your partner’s need for reassurance.

Conflict becomes less threatening when approached as collaboration rather than combat. Try the speaker-listener technique: one person speaks without interruption while the other reflects back what they heard before responding. This slows down escalation and creates safety.

Small daily connections matter more than grand gestures. Brief moments of eye contact, a gentle touch, or checking in about your partner’s day build security through consistency. These micro-moments of connection gradually rewire the nervous system to expect reliability rather than disappointment.

Comments

Loading…