10 Things Kids Say That Signal They Need Emotional Support

Children don’t always cry out for help with words we recognize—sometimes, their most urgent needs are hidden in the everyday things they say. A simple “I don’t want to go to school” or “I’m so dumb” might seem harmless, but these phrases can be quiet cries for emotional support. Kids often lack the vocabulary to express complex feelings, so their distress slips through in unexpected ways. As caregivers, educators, or parents, tuning into these subtle verbal cues is vital. Here are 10 common things kids say that may seem ordinary—but actually signal they’re struggling and need your attention and care.

1. “I’m so stupid”

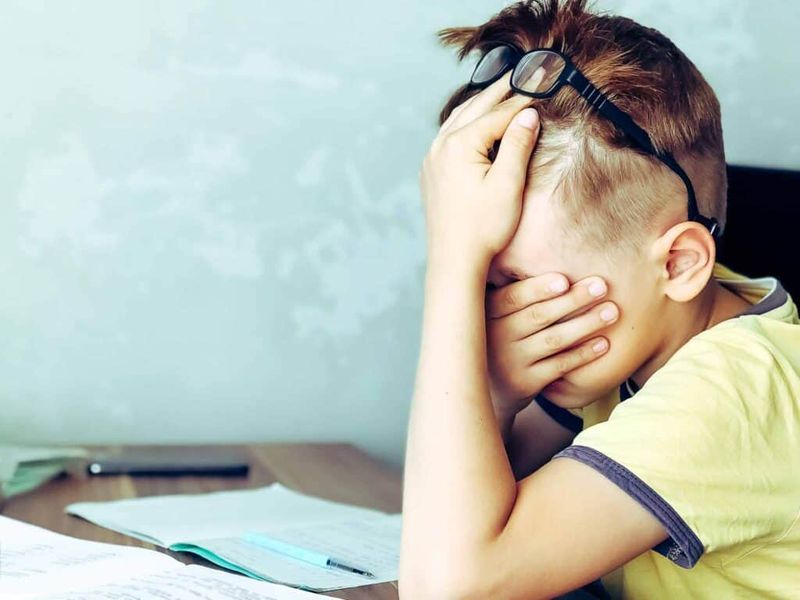

When a child labels themselves as “stupid” or “dumb,” they’re not just being hard on themselves—they’re expressing a wounded self-image that needs healing. These harsh self-judgments often emerge after making mistakes or facing challenges at school or home.

Children who use these self-critical words are typically experiencing anxiety, shame, or feeling overwhelmed by expectations. They’ve internalized negative messages and started believing them.

Respond by validating their frustration without validating the negative self-label. Say something like, “I see you’re feeling disappointed about that math problem. Everyone finds different things challenging. Let’s figure it out together.”

2. “No one likes me”

Social belonging is fundamental to a child’s wellbeing, making this phrase particularly heartbreaking. Children expressing this sentiment are revealing feelings of rejection, isolation, or difficulty connecting with peers.

Behind these words often lies a specific incident—perhaps exclusion from a game or birthday party—or ongoing social struggles. Sometimes, bullying or subtle forms of social exclusion are occurring without adults noticing.

Resist the urge to dismiss these feelings with quick reassurances like “That’s not true!” Instead, create space for them to share specific experiences: “That sounds really hard. Can you tell me about what happened today that made you feel that way?”

3. “I don’t want to go to school”

School refusal rarely happens without reason. This common phrase often masks specific fears—academic struggles, friendship problems, bullying, or separation anxiety. The morning complaints might actually represent a genuine emotional hurdle.

Physical symptoms like stomachaches or headaches frequently accompany this resistance, as anxiety manifests physically in children. Pay attention to patterns—does this happen on certain days or before specific classes?

Approach with curiosity rather than frustration: “I notice school has been tough lately. What part of the day feels hardest?” This opens conversation without judgment. Working with teachers to identify specific triggers can help develop targeted support strategies.

4. “I feel sick”

Children’s bodies often express what their words cannot. Recurring complaints of stomachaches, headaches, or feeling unwell—especially when medical causes have been ruled out—frequently signal emotional distress. These physical symptoms are genuine, not fabricated for attention.

The mind-body connection is particularly strong in children who haven’t developed sophisticated emotional vocabulary. Their nervous systems respond to stress by creating real physical sensations.

Instead of dismissing these complaints, acknowledge them while gently exploring emotional triggers: “Your tummy hurts again this morning. I wonder if something’s worrying you about today?” Teaching children to recognize the connection between feelings and physical sensations helps them develop emotional awareness.

5. “I hate everyone”

This dramatic declaration usually isn’t about hatred at all—it’s a protective shield. Children who make sweeping negative statements are often processing overwhelming feelings they don’t know how to express more precisely.

Behind this hostile façade typically lies hurt, rejection, disappointment, or feeling misunderstood. The child has experienced something painful and is retreating into anger as self-protection.

Rather than challenging the statement directly, acknowledge the intensity of their feelings: “Sounds like you’re having some really big feelings right now.” Then offer presence without pressure: “I’m here when you’re ready to talk.” This respects their emotional process while keeping the door open for connection when they’re ready.

6. “What’s wrong with me?”

This heartfelt question reveals a child grappling with their sense of self and place in the world. It often emerges after comparison with peers, experiencing repeated failures, or feeling different in some way that matters to them.

Children asking this question are trying to understand their unique challenges, whether academic, social, or emotional. They’re seeking reassurance that their differences don’t make them less worthy or lovable.

Respond with genuine curiosity: “What makes you wonder that?” followed by affirmation of their inherent worth: “Everyone has different strengths and challenges. Your brain/body works in its own wonderful way.” Highlight specific strengths while normalizing struggles as part of being human.

7. “I wish I wasn’t here”

Any statement suggesting a wish not to exist deserves our most serious and compassionate attention. Children rarely make such statements for manipulation—they’re expressing profound emotional pain that feels unbearable to them.

While not all such statements indicate suicidal intent, they always signal significant distress. The child feels trapped, overwhelmed, or unable to see how their situation could improve.

Respond calmly but directly: “That sounds like you’re feeling really terrible right now. I care about you and want to understand more.” Ask clarifying questions without judgment, seeking professional help promptly. Creating safety means taking these statements seriously while reassuring the child that painful feelings can change with proper support.

8. “I’m always messing up”

Perfectionism often appears early in childhood, particularly among sensitive or high-achieving kids. This statement reveals a painful gap between a child’s internal standards and their perceived performance.

Children expressing this sentiment typically experience disproportionate distress over minor errors. They’ve developed a thinking pattern where mistakes feel catastrophic rather than instructive.

Help reframe their relationship with mistakes: “Making mistakes is actually how our brains grow stronger—it’s called learning!” Share examples of your own errors and what you learned. Praise effort and improvement rather than perfect outcomes: “I noticed how you kept trying different approaches to solve that problem—that’s what successful people do!”

9. “I can’t do anything right”

This statement reveals a child drowning in self-doubt and possibly showing early signs of depression. Unlike occasional frustration, this global negative self-assessment suggests a pattern of hopelessness about their abilities.

Children expressing this sentiment often feel overwhelmed by expectations or repeated experiences of criticism. They’ve begun to see themselves through a distorted lens where successes are minimized and failures magnified.

Respond by gently challenging the all-or-nothing thinking: “I understand you feel that way right now, but let’s look at the evidence together.” Help them create a balanced perspective by identifying specific strengths and accomplishments. Consider whether pressure from school, home, or comparison with siblings might be contributing to this harmful self-perception.

10. “Leave me alone”

While everyone needs space sometimes, frequent or intense requests to be left alone can signal emotional flooding. Children who push others away are often protecting themselves from feelings they can’t manage.

This withdrawal might follow conflict, embarrassment, disappointment, or sensory overload. The child feels safer in isolation than risking further emotional discomfort through connection.

Respect their need for space while staying emotionally available: “I’ll give you some time to yourself, and I’ll be in the kitchen when you’re ready to talk.” For younger children, offering quiet presence nearby can help: “I’ll just sit here quietly while you take the space you need.” This balance respects their boundaries while preventing complete disconnection.

Comments

Loading…