16 Emotional Defenses We Learn to Build Before We Even Turn 10

Children are natural survivors, and their minds develop clever ways to protect them from overwhelming emotions long before they can even explain what they’re feeling. From the playground to the dinner table, kids unconsciously build invisible shields that help them cope with stress, disappointment, and confusion. Understanding these early emotional defenses can help us recognize patterns in our own adult behavior and support the young people in our lives with greater compassion.

1. Denial

When reality feels too painful to face, young minds simply refuse to acknowledge it exists. A child whose pet dies might insist the animal is just sleeping or will come back tomorrow.

This instinctive response acts like a temporary bandage over a wound that’s too big to process all at once. Kids use denial to buy themselves time until they’re emotionally ready to handle difficult truths.

While helpful in small doses, relying too heavily on denial can prevent children from learning to process grief and disappointment. Parents can gently guide kids toward acceptance without forcing them to confront overwhelming emotions before they’re ready.

2. Repression

Our brains have an incredible ability to hide memories that hurt too much to remember. A traumatic doctor visit or scary incident at school might completely vanish from a child’s conscious awareness, tucked away in a mental vault.

Unlike denial, which is a conscious refusal, repression happens automatically without the child even knowing it’s occurring. The memory doesn’t disappear—it just becomes inaccessible, like a file stored in a locked drawer.

These buried experiences can resurface later in life, sometimes triggered by similar situations. Therapy and safe conversations can help children process difficult experiences before they become deeply repressed.

3. Projection

Ever notice how a child who’s actually jealous might accuse their sibling of being jealous instead? That’s projection in action—attributing your own uncomfortable feelings to someone else makes those feelings easier to handle.

Young kids haven’t yet developed the self-awareness to recognize complex emotions within themselves. By placing those feelings onto others, they create emotional distance from what’s really bothering them.

A child struggling with anger might constantly complain that everyone else is mad at them. Helping kids identify and name their own emotions reduces their need to project feelings outward onto friends and family.

4. Displacement

When you can’t express anger toward someone powerful or scary, you find a safer outlet. The child who’s furious at a teacher but can’t say so might come home and snap at a younger sibling or kick their backpack across the room.

Displacement allows children to release intense emotions without risking punishment or rejection from authority figures. The original target feels too dangerous, so the feeling gets redirected toward something less threatening.

Parents often see this after difficult school days or stressful events. Recognizing displacement helps adults respond with understanding rather than punishment, addressing the root cause instead of just the misdirected behavior.

5. Regression

Stressed-out kids sometimes travel backward in time, returning to behaviors they’d outgrown. A potty-trained four-year-old might start having accidents again when a new baby arrives, or a seven-year-old might suddenly need a pacifier after moving to a new house.

These younger behaviors feel safe and comforting because they’re associated with simpler times when life felt more secure. Regression is the mind’s way of seeking comfort in familiar territory when the present feels too challenging.

Most regression is temporary and harmless. Responding with patience rather than frustration helps children feel secure enough to move forward again developmentally.

6. Rationalization

Kids become master excuse-makers when they need to protect their self-image. The child who didn’t study for a test might claim the questions were unfair or that everyone else cheated, creating logical-sounding reasons that make failure feel less personal.

Rationalization lets children maintain their self-esteem by reframing situations in ways that reduce guilt or shame. Instead of admitting they made a mistake, they construct explanations that shift responsibility elsewhere.

While everyone rationalizes occasionally, children who constantly make excuses may struggle with self-accountability. Teaching kids that mistakes are learning opportunities reduces their need to rationalize every misstep.

7. Sublimation

This is actually one of the healthier defenses! A child with aggressive impulses might become a star soccer player, transforming potentially destructive energy into something socially acceptable and even celebrated.

Sublimation takes uncomfortable feelings and redirects them into productive activities. The anxious child might pour energy into art projects, while the angry child finds release through competitive games.

Parents and teachers can encourage sublimation by helping children discover positive outlets for difficult emotions. Sports, music, art, and writing all provide healthy channels for feelings that might otherwise come out in problematic ways.

8. Intellectualization

Some children retreat into their heads when emotions feel too intense, focusing on facts and logic instead of feelings. A child dealing with their parents’ divorce might research statistics about family structures rather than crying about their sadness.

Intellectualization creates emotional distance by treating painful situations like academic problems to be analyzed. The child becomes a detached observer rather than an affected participant in their own life.

While intelligence and curiosity are wonderful, hiding behind facts prevents genuine emotional processing. Encouraging children to name and express feelings alongside their analytical thinking promotes healthier emotional development.

9. Fantasy

When real life feels disappointing or scary, children escape into elaborate imaginary worlds where they have control and power. The bullied child becomes a superhero in their mind, the lonely child invents invisible friends who never leave.

Fantasy provides temporary relief from harsh realities that feel unchangeable. In imagination, kids can rewrite their stories, becoming the hero instead of the victim.

Imaginative play is healthy and normal, but excessive fantasy that interferes with real-world engagement signals a child who needs support. Balancing imagination with tools for handling actual problems helps kids stay grounded while still enjoying creative play.

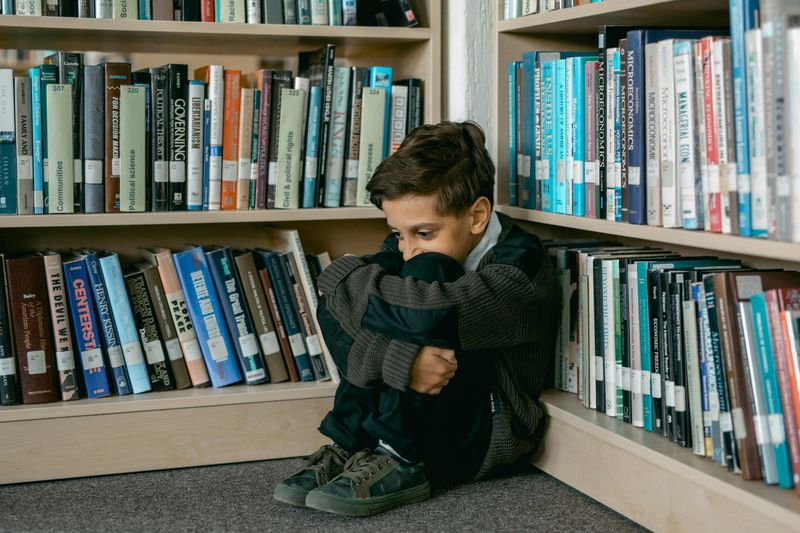

10. Avoidance

Sometimes the simplest defense is just staying away from whatever triggers uncomfortable feelings. The child who was embarrassed during show-and-tell might suddenly develop stomachaches every time it’s their turn to share.

Avoidance provides immediate relief from anxiety-provoking situations, which reinforces the behavior. Each successful avoidance teaches the child that staying away equals feeling better, even though it limits their growth.

While protecting children from genuine threats is important, helping them gradually face manageable fears builds resilience. Gentle exposure combined with coping strategies teaches kids they’re stronger than their anxieties suggest.

11. Humor

The class clown isn’t always just naturally funny—sometimes humor becomes armor against vulnerability. Making others laugh keeps attention on the jokes rather than on painful feelings hiding underneath.

Humor can be a wonderful coping mechanism when used alongside genuine emotional expression. However, kids who constantly deflect with jokes may be avoiding deeper feelings they don’t know how to process.

Did you know? Many professional comedians report using humor as children to cope with difficult home situations. Encouraging kids to be funny while also creating space for serious conversations helps them develop emotional range beyond just making people laugh.

12. Identification

Children often cope with feeling small and powerless by adopting characteristics of people they perceive as strong. A child afraid of the dark might imitate a brave character from their favorite show, borrowing that courage.

Identification helps kids feel more capable by mentally merging with someone they admire. By acting like their hero, they temporarily access feelings of strength and confidence that don’t yet come naturally.

This defense becomes problematic when children identify with negative role models or lose their own sense of identity. Helping kids recognize their own unique strengths reduces excessive dependence on borrowed confidence from others.

13. Reaction Formation

Sometimes feelings are so unacceptable that children flip them completely around. The child who’s jealous of a new sibling might become overly affectionate and protective, transforming resentment into its opposite to avoid guilt.

Reaction formation takes an uncomfortable emotion and expresses its reverse, often in exaggerated ways. The intensity of the opposite feeling actually reveals the strength of the hidden emotion underneath.

These extreme reversals can confuse both the child and the adults around them. Creating safe spaces where all feelings are acceptable reduces the need to hide true emotions behind their opposites.

14. Compartmentalization

Kids develop mental filing systems, keeping different parts of their lives completely separate. A child might act perfectly happy at school while dealing with serious problems at home, never letting the two worlds touch.

Compartmentalization allows children to function in one area even when another area is falling apart. By creating mental walls between different life domains, they prevent distress from spreading everywhere.

While this can help kids maintain stability, excessive compartmentalization prevents integration of experiences and authentic self-expression. Helping children understand that people can hold multiple feelings simultaneously promotes healthier emotional wholeness.

15. Passive Aggression

When direct anger feels too risky, children find sneaky ways to express resistance. The child asked to clean their room might move impossibly slowly, forget instructions repeatedly, or do such a poor job that someone else has to redo it.

Passive aggression lets kids express anger indirectly, avoiding the consequences of open defiance while still asserting some control. The behavior communicates frustration without the vulnerability of honest confrontation.

This pattern often develops when children fear punishment for expressing anger directly. Creating environments where respectful disagreement is allowed reduces the need for these indirect expressions of frustration.

16. Compensation

Feeling inadequate in one area drives some children to become exceptional in another. The child who struggles academically might become a star athlete, or the socially awkward kid might develop extraordinary artistic talent.

Compensation helps children maintain self-esteem by proving their worth in alternative domains. By excelling somewhere, they counterbalance feelings of failure elsewhere, creating a more positive overall self-image.

While developing strengths is wonderful, compensation becomes problematic when children use achievement to avoid addressing genuine difficulties. Balanced support helps kids improve weaknesses while celebrating strengths, reducing the pressure to be perfect in any single area.

Comments

Loading…