A painting carries more than likeness. Each brushstroke offers a version of womanhood shaped by beauty standards, social roles, and the artist’s perspective. In these 10 portraits, reality and expectation merge into an idealized vision. But beyond the surface, they reveal the ways history carved women into figures suited to its own storytelling.

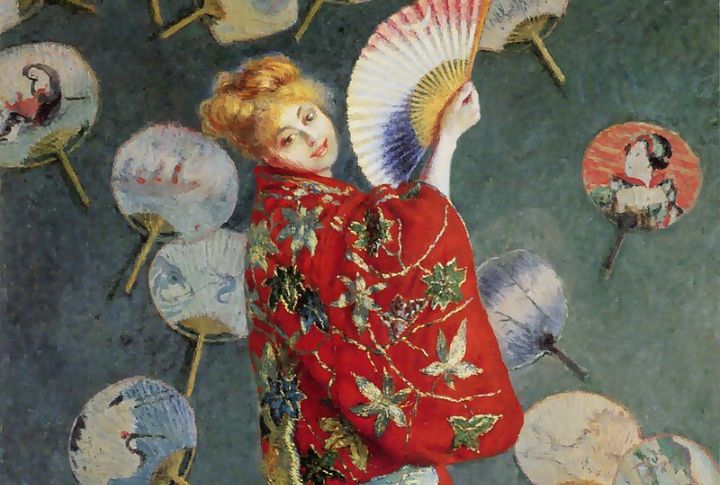

The Japanese Woman

Monet’s fascination with Japonisme reached its height in his portrait of Camille, draped in a striking red kimono. Ornate patterns and stylized gestures showcase a Western reimagining of Eastern aesthetics. More than a portrait, this work reflects the evolving dialogue between cultures, where admiration turns into artistic reinterpretation.

Madame X

Confidence and controversy collide in John Singer Sargent’s 1884 portrait of Virginie Amelie Avegno Gautreau. Her daring black gown and pale complexion shocked audiences, causing an uproar at the Paris Salon. The original painting featured a slipping shoulder strap, later adjusted to soften the scandal. Yet, the controversy only made her unforgettable.

Black Woman With Peonies

Found within the painting and hidden behind the softness of the peonies is a quiet challenge to 19th-century ideals. Frederic Bazille’s 1870 portrait breaks from traditional European beauty standards by portraying a Black woman—an uncommon subject for the time—whose presence defies artistic conventions and transforms the narrative of historical portraiture.

The Lady In White

Marie Bracquemond’s “The Lady in White” is more than a study in light. It portrays quiet elegance and presence. The subject stands with understated confidence, neither performing nor seeking attention. In an era of rigid expectations, Bracquemond captures grace beyond convention by allowing her subject to exist without spectacle or constraint.

Madame Moitessier

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres spent years perfecting Madame Moitessier’s regal presence. Her gaze, modeled after Roman wall paintings, emphasizes her elegance and high social rank. With smooth brushwork and exacting detail in her silk gown and jewelry, he reveals a woman who holds her space with ease.

The Bath

Mary Cassatt rejected grand portraiture to honor intimate, everyday moments. In her scene of a mother bathing her child, soft colors and gentle gestures reflect Impressionism’s quiet realism. The work honors human connection over ceremonial moments and draws viewers into a tender ritual that feels softly familiar.

Lady Lilith

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Lady Lilith” represents Victorian ideals of beauty and power. With cascading hair and an unwavering gaze, she is both alluring and untouchable. Rossetti’s portrayal transforms Lilith into a symbol of feminine mystique. She commands attention with ease, yet her intentions remain veiled behind that enigmatic stare.

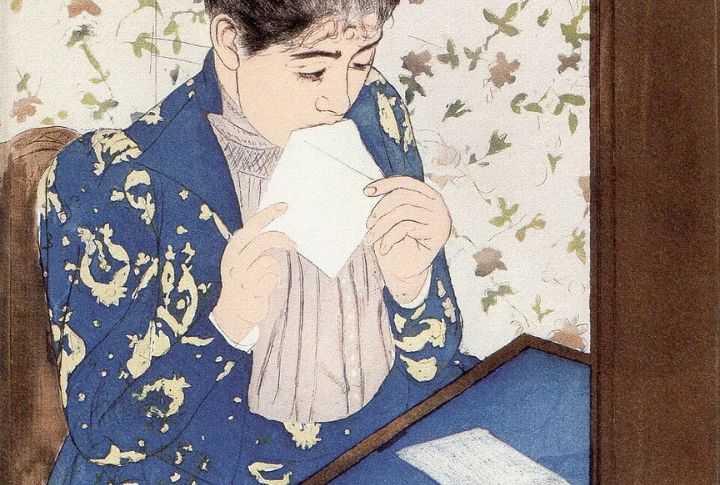

The Letter

Mary Cassatt captures yet another personal moment—a woman absorbed in writing. The delicate composition, influenced by Japanese prints, emphasizes solitude and introspection. Unlike grand portraits, “The Letter” focuses on the subject’s inner world. Through pen and paper, she claims a private space rarely afforded to women.

Young Girl At A Window

Berthe Morisot’s painting captures a brief moment of contemplation. A young woman gazes outward, suspended between presence and longing. Soft brushstrokes blur the boundary between interior and exterior and echo the Impressionist pursuit of light and motion. What she sees remains unknown, but her inner world takes center stage.

Woman With A Pearl Necklace

Mary Cassatt doesn’t present a subject on display; she reveals a woman absorbed in her own world. A pearl necklace, softly rendered, becomes the focal point and an emblem of quiet ritual. The scene offers no performance, only a moment of solitude shaped by Cassatt’s belief in the dignity of the everyday.

Comments

Loading…