15 Things TV Moms Did in the ’50s That Are Long Gone

The 1950s television mom shaped how America viewed motherhood for generations. These perfectly coiffed women in crisp aprons set impossible standards while reinforcing traditional gender roles. Looking back now, it’s almost unbelievable what these fictional mothers represented compared to today’s more realistic portrayals.

1. Full-Time Homemakers Without Question

Not a single TV mom in the 1950s held a job outside the home. Characters like Margaret Anderson from “Father Knows Best” dedicated every waking moment to maintaining household perfection without complaint or career aspirations. T

he idea that a mother might want professional fulfillment simply didn’t exist in these shows. When June Cleaver from “Leave It to Beaver” wasn’t cooking or cleaning, she was planning meals or waiting for family members to return home. The economic reality that many actual 1950s women worked outside the home was completely erased from television, creating a fantasy domestic ideal that influenced real-life expectations for decades.

2. Camera-Ready Appearance 24/7

TV moms like Donna Reed never had a hair out of place, even while scrubbing floors. Their perfectly pressed dresses, high heels, and pearl necklaces remained immaculate through cooking, cleaning, and child-rearing crises. Morning scenes featured these mothers already fully made-up with styled hair before the rest of the family awoke.

The contrast between television and reality was stark – real women didn’t vacuum in heels and pearls. This unrealistic standard created pressure that lingers today. Though modern shows now occasionally depict mothers in casual clothes with messy hair, the ’50s TV mom’s perfect appearance established impossible beauty standards for generations.

3. Sanitized Language and Topics

Swear words? Sex talk? Contraception? Absolutely forbidden in the world of 1950s TV mothers. Lucy Ricardo from “I Love Lucy” could become pregnant on screen, but the word “pregnant” was deemed too explicit for television – they used “expecting” instead.

Mothers maintained pristine vocabularies limited to gentle exclamations like “Oh my!” or “Goodness gracious!” Adult topics were either heavily coded or completely absent from scripts. Even marital intimacy was represented by separate twin beds for parents. This sanitized portrayal created a fantasy world where mothers remained perpetually innocent and childlike, denying them adult complexity and realistic human expression.

4. Trivial Problems Wrapped Up Neatly

Missing cake ingredients or children’s minor squabbles constituted the biggest crises 1950s TV moms faced. Every problem wrapped up tidily before the credits rolled, usually with a gentle life lesson delivered with a smile. Margaret Anderson of “Father Knows Best” never dealt with serious issues like financial struggles, illness, or relationship breakdown.

Real problems like alcoholism, abuse, or mental health challenges simply didn’t exist in these sanitized households. The formula created a fantasy world where maternal wisdom (or sometimes father’s intervention) could solve anything in 30 minutes. This unrealistic conflict resolution pattern established expectations that real-life problems should resolve quickly and painlessly.

5. Pregnancy as Comedy or Invisible Experience

When Lucille Ball’s real-life pregnancy was incorporated into “I Love Lucy,” it became a sensation – yet the word “pregnant” remained taboo. The physical realities of pregnancy were either played for laughs or completely hidden from viewers. Most TV moms’ pregnancies involved comical cravings or fathers nervously pacing. Morning sickness, body changes, and discomfort were deemed unsuitable for family viewing.

The actual birth always happened offscreen, with mothers returning home looking immaculate. This sanitized portrayal denied the physical realities women experience. By treating pregnancy as either invisible or comedic, these shows reinforced the idea that women’s bodily experiences should remain private or trivialized.

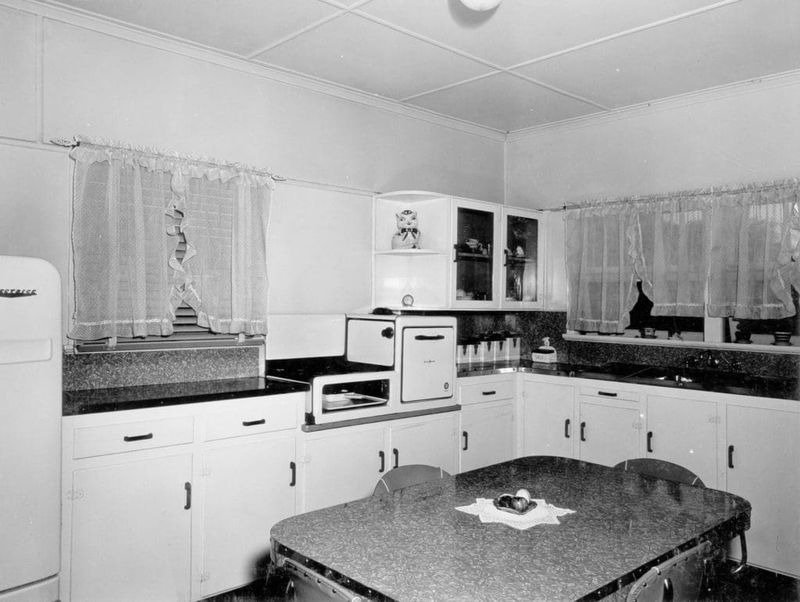

6. Spotless Homes Without Effort

The kitchens of June Cleaver and Harriet Nelson gleamed with supernatural cleanliness. Countertops sparkled, floors shined, and not a dish remained unwashed for more than a scene or two. These TV moms performed housework, but the true labor involved was magically minimized. Scenes might show them dusting ornaments delicately but never scrubbing toilets or battling stubborn stains.

The physical toll of maintaining such perfection was completely erased. This portrayal created impossible standards while diminishing the real work of homemaking. Modern shows now occasionally acknowledge mess as normal, but the legacy of the spotless ’50s TV home continues to shape expectations about women’s domestic responsibilities.

7. Divided Parental Roles

“Wait until your father gets home!” This familiar threat from ’50s TV moms revealed the strict division of parental labor. Mothers handled minor infractions with gentle scolding, while fathers delivered serious discipline. The mother’s role was emotional caretaking and household management. Margaret Anderson of “Father Knows Best” might comfort an upset child, but Jim Anderson had the final word on important decisions.

These shows portrayed mothers as nurturing but ultimately subordinate to paternal authority. This rigid gender division influenced real families for generations. Modern shows now depict more balanced parenting approaches, but the stereotype of mothers as soft disciplinarians and fathers as ultimate authorities originated largely from these influential ’50s portrayals.

8. Isolation from Social Issues

Civil rights movements, Cold War tensions, and women’s changing roles dramatically shaped 1950s America, yet TV moms existed in bubbles untouched by social change. These characters never discussed politics, racial inequality, or world events affecting actual families. Shows like “Leave It to Beaver” portrayed an idealized America where mothers focused exclusively on domestic concerns.

The Montgomery bus boycott might be happening in real life, but June Cleaver’s biggest worry remained Beaver’s latest mishap. This deliberate avoidance reinforced the idea that “good mothers” shouldn’t engage with complex social issues. By separating motherhood from citizenship and social awareness, these portrayals limited women’s perceived roles to purely domestic spheres.

9. Exclusively White, Middle-Class Families

The TV mom landscape of the 1950s was strikingly homogeneous. Every mother was white, married to a successful husband, and comfortably middle-class with a single-family home in the suburbs. Families like the Cleavers and Andersons represented a narrow slice of American life presented as universal. Single mothers, working-class families, and people of color were almost completely absent from domestic sitcoms.

When non-white characters appeared at all, they were relegated to servant roles. This whitewashed portrayal erased the diversity of actual American families. By presenting only one family model as normal and desirable, these shows reinforced harmful hierarchies while denying representation to millions of viewers whose lives didn’t match the idealized version.

10. No Personal Interests Beyond Family

TV moms of the ’50s existed solely to serve their families’ needs. Characters like Donna Stone from “The Donna Reed Show” never pursued hobbies, education, or personal interests unrelated to homemaking or child-rearing. These mothers didn’t join book clubs, take classes, or develop skills for personal satisfaction.

Their happiness derived exclusively from family success and domestic harmony. Any hint of personal ambition outside the home was portrayed as selfish or unwomanly. This one-dimensional portrayal denied women’s natural need for identity beyond motherhood. Modern shows now routinely show mothers with careers, friendships, and interests, but the ’50s stereotype of the mother whose world revolves entirely around her family continues to influence expectations.

11. Product Placement Perfection

The gleaming appliances in ’50s TV kitchens weren’t just props – they were advertisements. Shows featured the latest refrigerators, mixers, and vacuum cleaners as symbols of modern motherhood and American progress. TV moms like Harriet Nelson operated these products with delighted amazement, their domestic work magically simplified by consumer goods. The not-so-subtle message: good mothers embraced new household technology.

These programs functioned partly as showcases for postwar consumer culture. This commercialization of motherhood created pressure to purchase specific products as proof of good homemaking. The legacy continues today in mommy blogs and social media, where particular brands and items still symbolize maternal competence.

12. Children Who Learned Neat Lessons

In the world of ’50s TV moms, children misbehaved in minor, adorable ways that set up tidy moral lessons. Mothers like June Cleaver guided their children through gentle conversations that inevitably led to perfect understanding and behavior change. These fictional children never faced serious problems like bullying, learning disabilities, or identity struggles.

Their mistakes were simplistic plot devices designed to demonstrate parental wisdom rather than realistic childhood experiences. By the episode’s end, Beaver Cleaver or Bud Anderson would have internalized the moral lesson completely. This unrealistic portrayal created expectations that good mothers could solve any childhood issue with a single conversation, setting real mothers up for feelings of inadequacy.

13. Invisible Domestic Help

The spotless homes of ’50s TV moms often relied on unseen help. Shows occasionally featured maids or housekeepers, almost always women of color, who appeared briefly to assist the white mother without recognition of their own family lives or struggles. Characters like Beulah from the show of the same name were presented as happy to serve white families.

Their portrayal reinforced racial hierarchies while downplaying the reality that maintaining picture-perfect homes required substantial labor. This erasure of domestic workers’ humanity served a dual purpose: maintaining the myth that mothers could effortlessly manage perfect homes while reinforcing racial and class divisions. The contributions of household workers were simultaneously essential yet marginalized in these fictional worlds.

14. Feminine Rights? What Rights?

The feminist movement was gaining momentum in 1950s America, yet TV moms existed in a parallel universe where women’s rights weren’t mentioned. Characters like Margaret Anderson never questioned their limited roles or lack of legal and financial independence. These fictional mothers never discussed voting choices, property rights, or workplace discrimination.

Their contentment with domestic confinement was presented as natural rather than socially constructed. Any hint of feminist awareness would have disrupted the comfortable fantasy these shows maintained. By erasing women’s political consciousness, these portrayals reinforced the idea that “good mothers” accepted traditional limitations without question. This deliberate omission helped slow real-world progress by normalizing women’s second-class status.

15. Baby Talk and Saccharine Sentiment

The dialogue of ’50s TV moms dripped with exaggerated sweetness and infantilizing language. These mothers spoke to their husbands using childish nicknames and expressed emotions through syrupy clichés rather than authentic communication. Donna Reed might call her husband “darling” a dozen times per episode while avoiding substantive conversations about real feelings.

Conflicts resolved through sentimental platitudes rather than honest discussion. This artificial sweetness created a caricature of femininity that valued pleasantness above authenticity. The baby talk and saccharine expressions reinforced the infantilization of women. By portraying mothers as emotionally simplistic and childlike in their communication, these shows denied women’s intellectual and emotional complexity.

Comments

Loading…