10 Historical Figures Everyone Called Delusional—Until They Were Proven Right

It’s easy to laugh at someone who sees the world differently, especially when their ideas challenge “common sense” or threaten the comfort of what everyone already believes.

Across history, people who questioned the status quo were labeled unstable, delusional, arrogant, or just plain ridiculous, and that kind of name-calling wasn’t always harmless.

Careers were ruined, reputations were destroyed, and in some cases, lives were derailed simply because someone dared to insist that reality worked in a different way.

The twist is that many of those “crazy” claims weren’t fantasies at all; they were early glimpses of truths that the rest of society hadn’t caught up to yet.

These ten figures were dismissed in their time, but later evidence, science, and shifting cultural understanding proved they weren’t losing their minds.

They were ahead of them.

1. Aristarchus of Samos

Long before telescopes and modern physics, one Greek thinker dared to suggest something that sounded backwards to his contemporaries: the Earth might not be the center of everything.

In an era when the sky was interpreted through tradition, philosophy, and religious meaning, proposing that the Sun sat at the center of the universe could easily make a person look misguided or even reckless.

Aristarchus argued for a heliocentric model centuries before it had the mathematical tools and observational evidence needed to convince anyone else.

His idea was largely ignored, partly because the geocentric model fit everyday perception and already had respected intellectual backing.

Much later, astronomers like Copernicus and Galileo revived heliocentrism, and it eventually became the framework for modern astronomy.

What sounded “crazy” in ancient Greece became the starting point for how we understand space.

2. Galileo Galilei

Challenging the most powerful institutions of your time is a fast way to be branded dangerous, and Galileo found that out firsthand.

Even though he wasn’t the first to support heliocentrism, he was one of the first to bring compelling observational evidence to the argument, thanks to his work with the telescope.

When he reported moons orbiting Jupiter and phases of Venus, those discoveries didn’t just expand scientific knowledge; they contradicted the tidy, Earth-centered cosmos many authorities insisted must be true.

Critics framed him as arrogant, deceptive, or mentally unsteady, because accepting his findings meant admitting that long-held “certainties” were wrong.

He faced serious consequences for refusing to back down, yet history ultimately sided with him.

Modern astronomy rests on the very reality he insisted people look at, even when they didn’t want to.

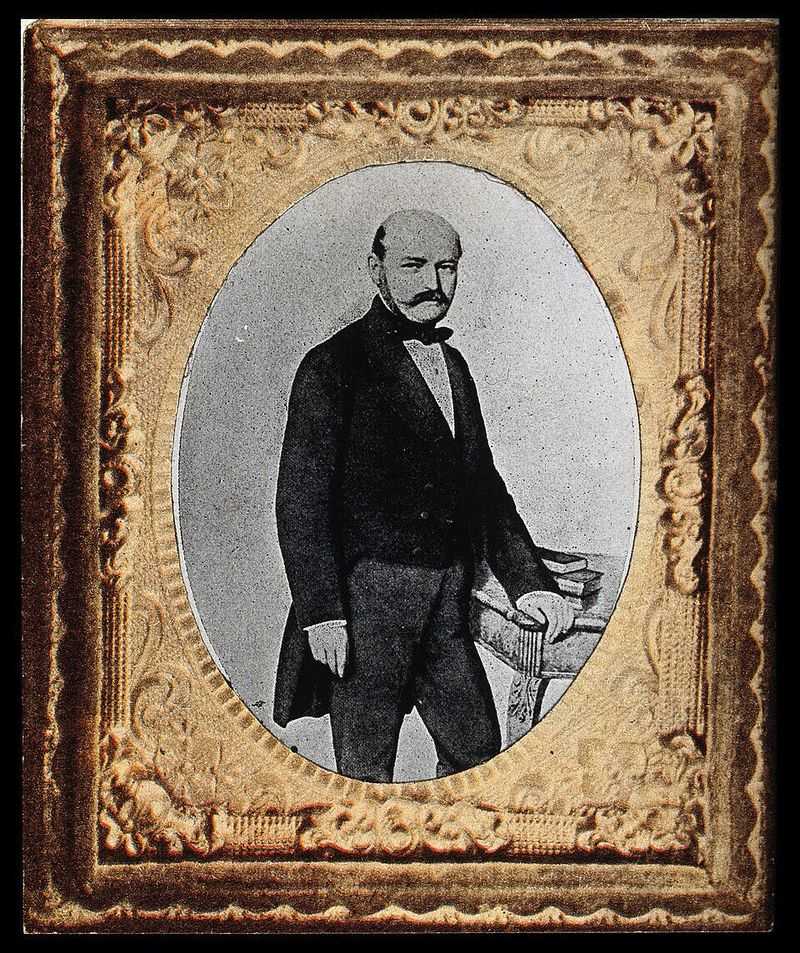

3. Ignaz Semmelweis

The idea that doctors could be causing infections sounds obvious now, but in the mid-1800s it was treated like an insult.

Semmelweis noticed that women in one maternity ward were dying at far higher rates than in another, and he traced the difference to medical staff who moved from autopsies to childbirth without washing their hands.

His solution was simple and effective—handwashing with disinfectant dramatically reduced deaths—but the medical establishment resisted because it implied they were responsible for harm.

Instead of being praised, he was mocked and dismissed as obsessive, irrational, and overly emotional.

Without a widely accepted germ theory at the time, many colleagues considered his conclusions unscientific.

Decades later, when germ theory gained support through scientists like Pasteur and Lister, Semmelweis’s insistence on hygiene was recognized as lifesaving truth, not madness.

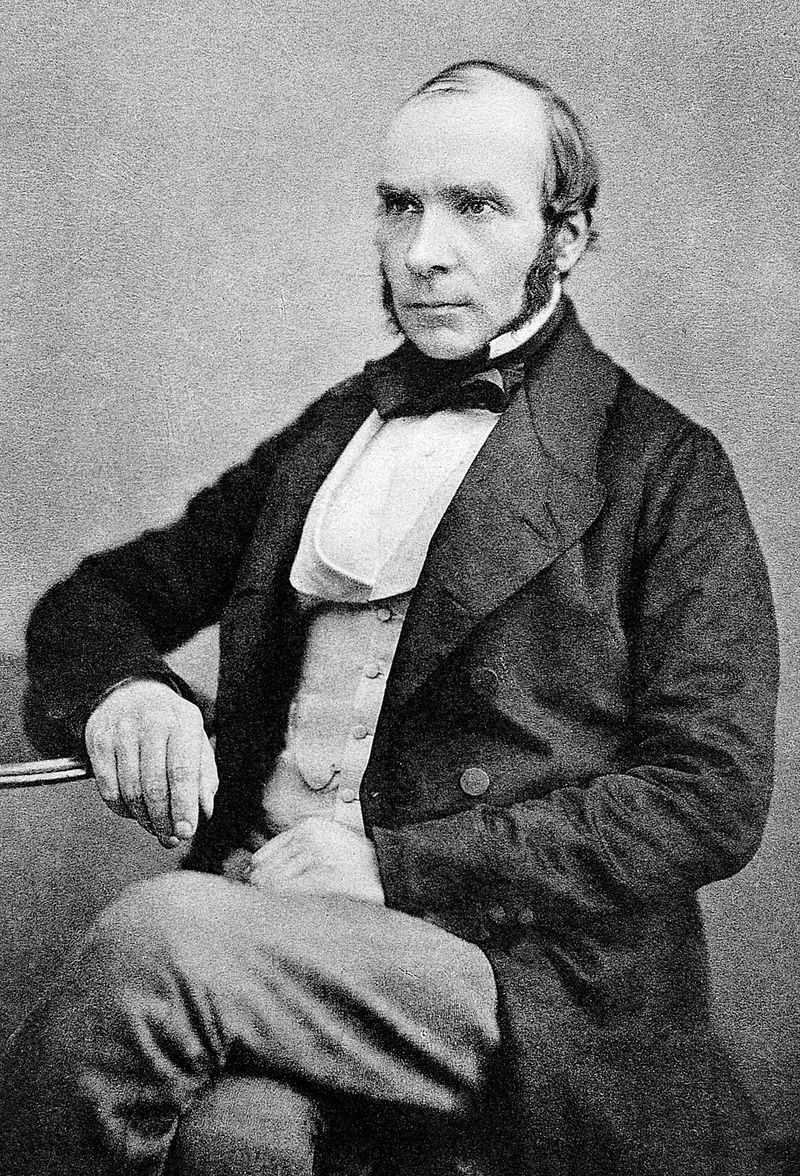

4. John Snow

During cholera outbreaks in 19th-century London, most people believed disease spread through “bad air,” which meant efforts focused on smells rather than sources.

Snow thought that explanation didn’t match the pattern he was seeing, and he pushed a controversial alternative: contaminated water was the real culprit.

He mapped cases, interviewed residents, and traced infections to a specific water pump on Broad Street, a method that looked suspiciously obsessive to critics who preferred established ideas.

Because he was challenging a widely accepted medical theory, his conclusions were dismissed as extreme and speculative, even though they were grounded in careful observation.

Removing access to the pump helped slow the outbreak, and over time his approach became a foundational moment in epidemiology.

Today, his work is praised for pioneering data-driven public health, even though it was once treated like an eccentric fixation.

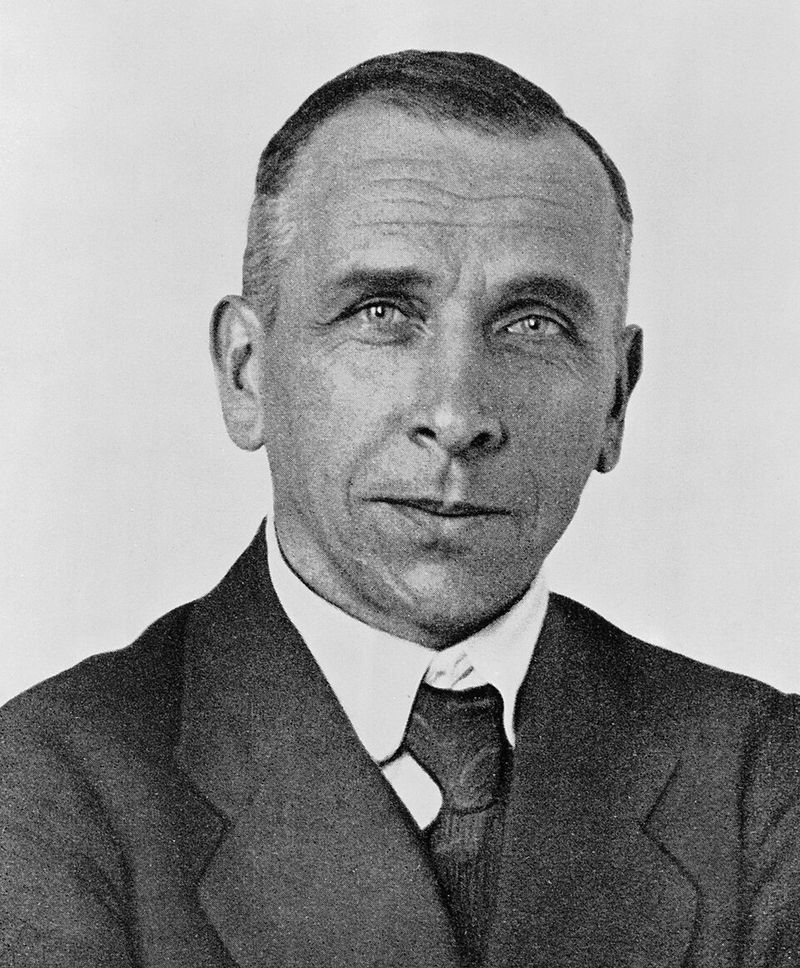

5. Alfred Wegener

When Wegener proposed that continents move, he wasn’t just offering a new theory; he was asking the scientific world to abandon a deeply comfortable assumption.

He pointed out that coastlines fit together like puzzle pieces and argued that continents had once been joined, then drifted apart over time.

The problem was that he couldn’t fully explain the mechanism behind the movement, and many geologists treated that gap as proof he was fantasizing.

Because he came from a background in meteorology rather than geology, critics were even quicker to dismiss him as an outsider with a bizarre obsession.

For decades, continental drift was treated like a crank idea, even though the evidence kept piling up.

Later discoveries about seafloor spreading and plate tectonics finally offered the “how,” and Wegener’s core insight became standard science.

What sounded ridiculous became geology 101.

6. Robert H. Goddard

A century ago, the thought of rockets traveling into space sounded like pure science fiction, and Goddard became a public target for daring to take it seriously.

When he discussed the possibility of reaching the Moon, some newspapers mocked him as naïve or detached from reality, treating the idea as proof that he didn’t understand basic physics.

The criticism wasn’t just mean; it reflected how people often react when something feels too big to imagine.

Goddard kept working anyway, developing liquid-fueled rocket technology and proving that controlled, powerful propulsion was possible.

His innovations laid groundwork that later programs, including those leading to space exploration, depended on.

The same concept that got him ridiculed became the backbone of modern aerospace engineering, and even his harshest critics eventually had to admit that he wasn’t dreaming.

He was building the future.

7. Hedy Lamarr

Fame can be a strange kind of trap, and Lamarr’s beauty and celebrity status caused many people to underestimate her intelligence.

While the public saw a glamorous Hollywood star, she was also a sharp inventor who worked on technology designed to protect wartime communications.

Along with composer George Antheil, she developed a frequency-hopping concept meant to prevent enemy forces from jamming radio-controlled torpedoes.

The idea sounded unusual, and because it came from someone the world didn’t take seriously as a technical mind, it was brushed aside and underused for years.

Yet the underlying principle—rapidly changing frequencies to reduce interference—turned out to be incredibly important as wireless technology advanced.

Variations of frequency hopping later influenced modern communication systems, including Wi-Fi and Bluetooth.

What people treated as a vanity project from an actress became a building block of how our devices talk to each other.

8. Lynn Margulis

Sometimes the boldest ideas sound wrong simply because they disrupt how we like to tell a neat story about evolution.

Margulis argued that complex life didn’t only arise through slow competition and random mutation, but also through cooperation at the cellular level.

Her endosymbiotic theory suggested that parts of our cells, like mitochondria, began as independent bacteria that formed a lasting partnership with other cells.

Many scientists initially rejected the claim, calling it far-fetched and overly imaginative, partly because it went against dominant evolutionary thinking at the time.

She faced repeated rejection and harsh criticism, yet she kept refining her argument and building evidence.

Over time, research in genetics and cell biology supported her view, and endosymbiosis became widely accepted.

The idea that once sounded like biology fan fiction is now a key explanation for how complex organisms exist at all.

9. Barry Marshall

Medical consensus can be stubborn, especially when it’s built on decades of assumptions that feel emotionally satisfying.

For a long time, ulcers were blamed on stress, personality, or spicy food, which also meant patients were often told to manage their emotions rather than look for a concrete cause.

Marshall argued that a bacterium—H. pylori—was responsible for many ulcers, and he was met with skepticism because it challenged a comfortable narrative.

To prove his point, he famously swallowed the bacteria himself, developed symptoms, and then treated the infection, a move that many people saw as reckless.

Over time, strong clinical evidence piled up, and treatment protocols shifted toward antibiotics and targeted care.

The discovery changed how ulcers are diagnosed and managed worldwide.

What once sounded like a bizarre, almost absurd claim became mainstream medicine, improving lives for millions who were previously blamed for their own illness.

10. Rachel Carson

Pointing out invisible dangers has a way of making a person seem hysterical to people who benefit from pretending everything is fine.

Carson warned that widespread pesticide use, especially DDT, was harming wildlife, contaminating ecosystems, and potentially threatening human health.

Because she was challenging powerful industries and popular postwar faith in “better living through chemistry,” critics framed her as emotional, unscientific, and irrational.

The backlash often focused on her tone rather than her evidence, which is a classic way society dismisses inconvenient truths.

Yet her research and arguments helped spark public debate, influenced environmental policy, and contributed to major changes in how pesticides were regulated.

Later scientific findings supported many of her concerns about bioaccumulation and ecological damage.

What detractors called alarmism became the foundation of modern environmental awareness, proving that sounding dramatic isn’t the same as being wrong.

Comments

Loading…