14 Actors Who Transformed Themselves In Extreme Ways for Iconic Roles

Hollywood loves to sell the idea that greatness requires suffering, and sometimes actors buy into that myth a little too hard.

A dramatic physical transformation can look impressive on a poster, and a “method” reputation can turn into free publicity, but the line between commitment and self-destruction is thinner than people think.

Some performers have pushed their bodies to extremes through drastic weight changes, punishing training schedules, and long shoots in brutal conditions, while others have taken the psychological route—staying in character so aggressively that the entire set has to deal with the fallout.

Not every extreme choice is necessary, and not every “real” moment on camera is worth what it costs behind the scenes.

Still, these stories have become part of movie lore, and they reveal how far certain stars will go to chase authenticity, awards, or a career-defining performance.

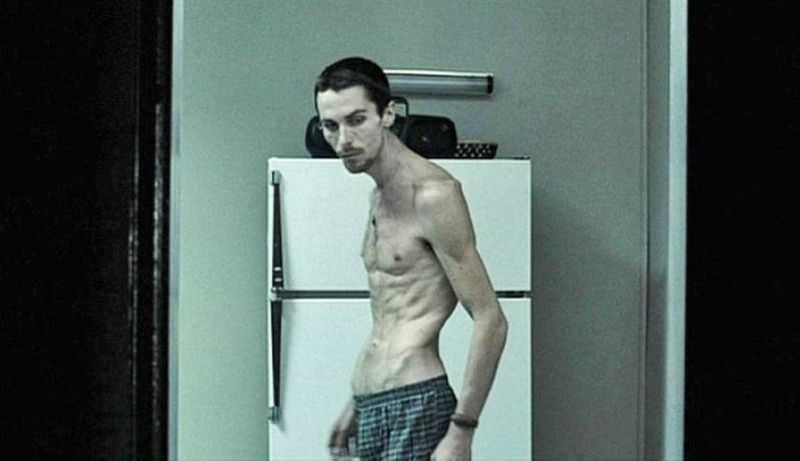

1. Christian Bale — The Machinist (2004) / Batman Begins (2005)

Few modern transformations are referenced as often as the one that made Bale look hauntingly skeletal in The Machinist.

The point wasn’t just “losing weight,” but creating a body that looked like it was barely holding together, which made every scene feel tense even before the dialogue landed.

What really tips this into “too far” territory is the whiplash that followed, because he then had to reverse course quickly for Batman Begins and rebuild mass for a superhero frame.

That kind of rapid swing is famous in Hollywood anecdotes, but it also carries real stress for the body, especially when it’s repeated across projects.

The result was unforgettable, yet it’s hard not to wonder whether the industry rewards extremes because it mistakes them for seriousness.

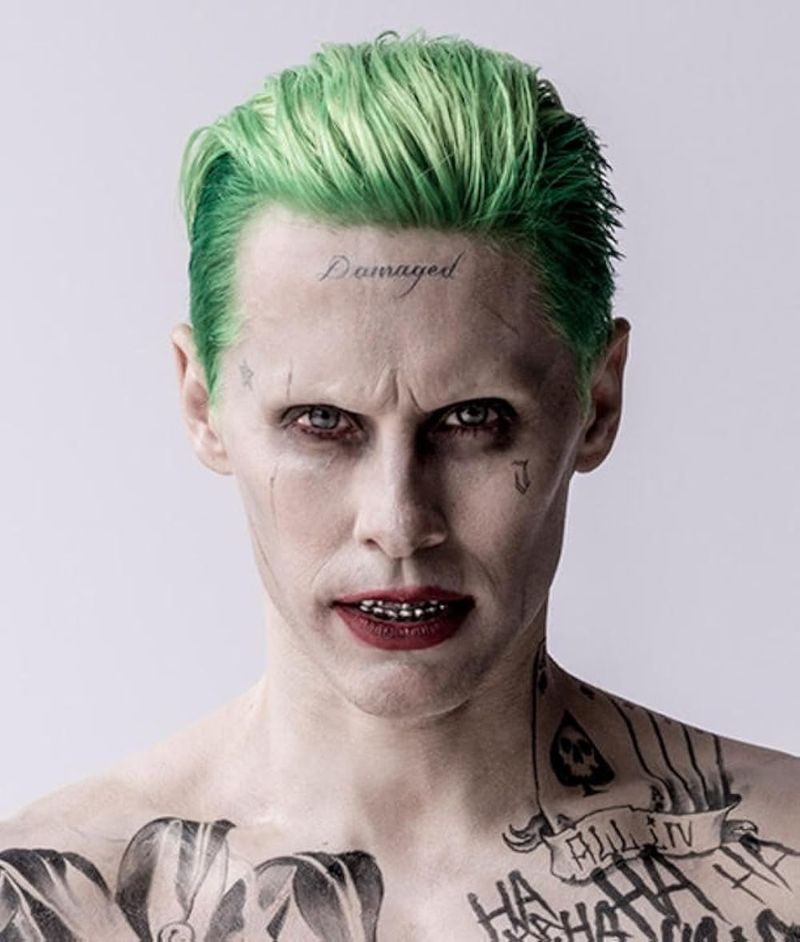

2. Jared Leto — Suicide Squad (2016)

Some actors disappear into a role on camera, while others try to make the entire production revolve around their persona off camera, too.

During Suicide Squad, Leto’s approach to playing the Joker became notorious because he leaned into a version of method acting that blurred into performance art and provocation.

Multiple cast and crew interviews over the years have described him staying in character and, according to reports, sending unsettling “gifts” as part of that commitment.

Even if the intention was to set a tone, the effect was that the boundary between acting and workplace comfort got messy.

The biggest irony is that the movie’s Joker is still a divisive take, which makes the extreme tactics feel less like dedication and more like unnecessary chaos.

If your process leaves everyone else stressed, it might be the process that needs rewriting.

3. Leonardo DiCaprio — The Revenant (2015)

The suffering in The Revenant doesn’t feel theatrical, and that’s partly because the production demanded a kind of endurance that most actors never touch.

DiCaprio filmed in harsh natural environments, dealt with freezing conditions, and pushed through long, exhausting shoots that relied on limited daylight.

One of the most talked-about moments is the raw animal liver scene, which he did on camera despite personal discomfort, because the film leaned hard into realism.

That willingness to endure physical misery helped create the movie’s “you can practically feel the cold” effect, but it also raises the question of how much pain should be treated as a badge of artistic honor.

The performance is powerful, yet the experience sounds like a survival challenge packaged as prestige cinema.

When authenticity becomes a dare, you start wondering who benefits most.

4. Tom Cruise — Mission: Impossible series (especially Ghost Protocol 2011 and Fallout 2018)

Blockbuster stunts usually come with a safety team, camera tricks, and a stunt double, which is exactly why Cruise’s insistence on doing so much himself stands out.

Hanging off skyscrapers, clinging to aircraft, and repeatedly chasing bigger set pieces has become his signature, and the franchise builds its marketing around “he really did it.”

That kind of commitment looks thrilling on screen, but the risk is not theoretical, because injuries have happened during filming and schedules have been impacted when something goes wrong.

What makes it feel like “too far” is how the bar keeps rising, as if the only way to top the last movie is to gamble with the next one.

The result is undeniably exciting, yet it also normalizes the idea that real danger is part of entertainment value.

At a certain point, the stunt stops being brave and starts being a liability.

5. Heath Ledger — The Dark Knight (2008)

Instead of relying on makeup and a creepy laugh, Ledger built the Joker from the inside out, turning the character into something disturbingly specific.

He worked on voice, posture, and unpredictable rhythm until the performance felt like it was constantly one step ahead of everyone else in the scene.

Stories from the production often highlight how intensely he focused on crafting the role, including isolating himself for stretches while developing the character’s mannerisms and mindset.

It’s important not to romanticize that intensity as the only path to greatness, because the industry can be too eager to turn struggle into legend.

Still, what he delivered is one of the most iconic performances in modern film, and it set a high bar for comic-book villains.

The “too far” element comes from how easily this kind of immersion becomes a template for others to copy without the same talent or support.

Great art shouldn’t require self-erasure.

6. Charlize Theron — Monster (2003)

Transformations are common in awards-season films, but Theron’s work in Monster is the kind that makes you forget you’re watching a movie star at all.

She gained weight, altered her appearance dramatically, and adopted physical details that made the character feel lived-in rather than “performed.”

The change wasn’t just cosmetic, because she leaned into a rawness that made the story uncomfortable in the way it needed to be, and the performance became the entire movie’s engine.

The reason it can feel like going too far is that Hollywood often rewards women most when they become unglamorous, as if the proof of talent has to be visible on the body.

Theron’s transformation is respected because it served a purpose, but it also highlights a weird industry standard: women are praised for “bravery” when they stop being polished.

She earned every accolade, yet it’s worth asking why an actress has to physically disappear to be taken seriously.

7. Matthew McConaughey — Dallas Buyers Club (2013)

A lot of actors lose weight for roles, but McConaughey’s change for Dallas Buyers Club was so drastic it became part of the conversation before people even saw the film.

His character’s illness required a body that looked like it was wasting away, and the visual impact is immediate, because it makes the story feel urgent without any exposition.

The challenge is that extreme weight loss is one of those commitments the public applauds while quietly ignoring the potential health consequences.

In this case, the transformation did help him disappear into the character and deliver a performance that shifted his career narrative into “serious actor” territory.

That’s also what makes it feel like the industry incentivizes the extreme, because a dramatic physical change often becomes shorthand for “this is important.”

The film’s success suggests it “paid off,” but that doesn’t make the path safe, or even necessary, for everyone trying to prove themselves.

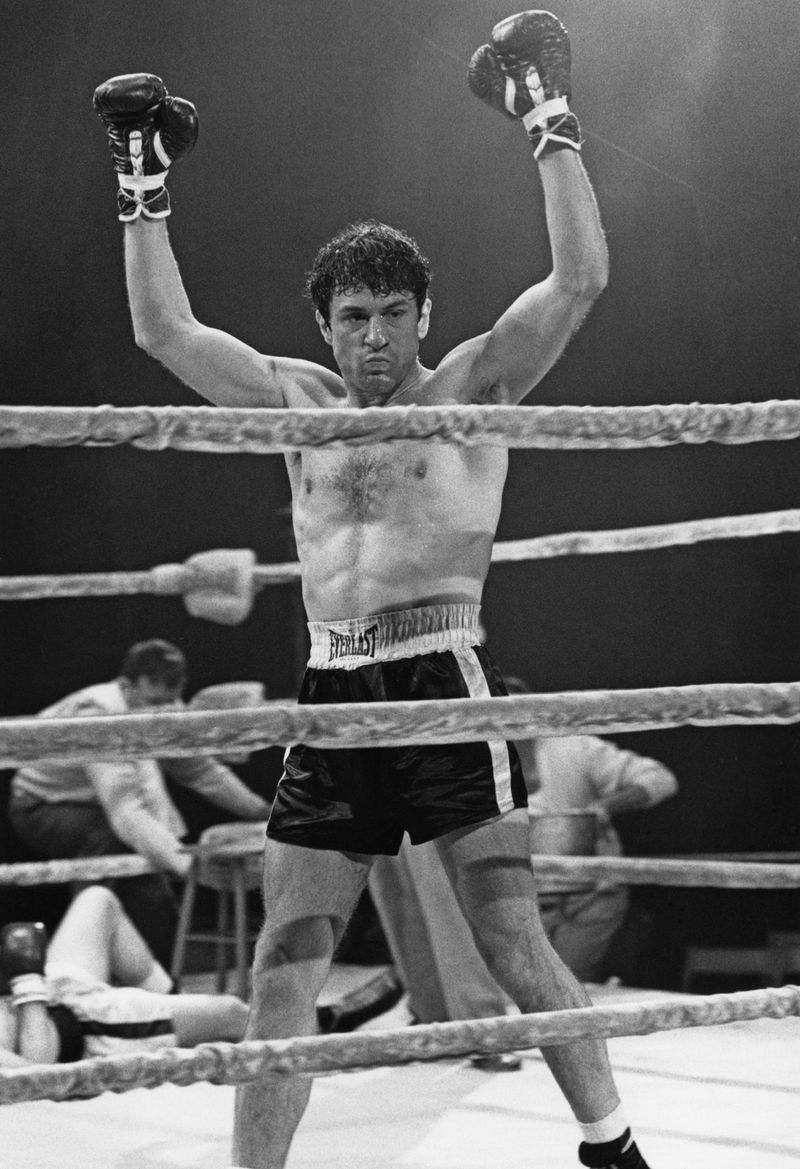

8. Robert De Niro — Raging Bull (1980)

Long before dramatic body changes became a trendy headline, De Niro set a template for extreme commitment by physically evolving across Raging Bull.

He didn’t just put on a little weight; he reshaped himself to convincingly portray Jake LaMotta at different stages, including the later-life version where the character looks heavy, worn down, and past his prime.

The dedication is legendary, and the results are part of why the film still feels brutally authentic decades later.

What makes it “too far” is the way such transformations can pressure actors to treat their bodies like props, especially when the industry praises the sacrifice more loudly than the craft.

De Niro’s acting is extraordinary even without the weight gain, which raises the uncomfortable thought that the physical extremity might be what people remember first.

The performance deserved acclaim, but the lesson Hollywood took from it sometimes seems wrong: bigger risk equals better art.

That’s not a rule, it’s a gamble.

9. Jim Carrey — Man on the Moon (1999)

Playing Andy Kaufman is already a tricky assignment, because the entire point of Kaufman’s persona was to keep everyone guessing about what was real.

Carrey took that ambiguity and turned it into a full-time approach on set, often staying in character as Kaufman—and sometimes as Tony Clifton—beyond the actual scenes.

Accounts from the production describe a chaotic atmosphere where the line between performance and disruption blurred, and the dedication became part of the movie’s legend.

This is where “too far” starts to show up, because acting is supposed to serve the story, not overwhelm the working environment for everyone else.

Carrey’s commitment did capture the spirit of Kaufman’s unpredictability, and the film feels more like a lived experience than a polished reenactment.

Still, there’s a difference between immersion and making your co-workers feel like they’re trapped inside your process.

If the set becomes a psychological experiment, it might not be art—it might just be exhausting.

10. Adrien Brody — The Pianist (2002)

The quiet devastation in Brody’s performance works because he looks and moves like someone whose world has collapsed, and he reportedly approached the role with a level of deprivation that went beyond normal preparation.

He lost a significant amount of weight and made lifestyle choices that emphasized isolation and austerity, which helped him embody the character’s loneliness and survival mindset.

The film’s emotional impact is undeniable, and the restraint in his acting makes the story even more crushing, because it avoids melodrama.

The “too far” question appears when preparation becomes a form of self-imposed suffering, especially when the subject matter is already heavy.

It can be tempting to believe you must feel miserable to portray misery convincingly, but that’s a dangerous shortcut that rewards pain over technique.

Brody’s performance became award-winning and career-defining, yet it also feeds the myth that the best acting requires a personal toll.

Sometimes the bravest choice is protecting your own stability while telling someone else’s story.

11. Natalie Portman — Black Swan (2010)

The physical precision of ballet is punishing even for trained dancers, which is why Portman’s transformation for Black Swan carries such a sense of intensity.

She underwent grueling dance training and conditioning to sell the role, and the performance depends on that work because the character’s obsession is expressed through the body as much as the dialogue.

The film’s tension comes from the sense that perfection is eating the character alive, and the preparation mirrored that theme in a way that feels both impressive and unsettling.

This is where “too far” becomes a real question, because extreme training can blur into injury risk and mental strain, especially when the story itself is about pressure and control.

Portman’s commitment helped create an iconic performance, yet it also shows how easily “dedication” becomes a euphemism for pushing yourself past reasonable limits.

When the job demands transformation, the industry rarely asks what it costs afterward, and it should.

12. Hilary Swank — Boys Don’t Cry (1999)

What makes Swank’s performance in Boys Don’t Cry so affecting is that it feels deeply inhabited rather than performed, which is often the result of meticulous preparation.

She transformed her appearance to convincingly portray Brandon Teena, including physical adjustments and behavioral details that shaped how she moved through every scene.

The film required sensitivity and realism, and her work avoids caricature by focusing on small, human choices that make the character feel present.

The “too far” edge comes from how emotionally demanding the story is, because stepping into a role rooted in trauma can linger long after the cameras stop.

When an actor commits to authenticity in a story like this, it can be difficult to separate empathy from emotional depletion, especially if the production doesn’t prioritize aftercare.

Swank’s performance became a landmark and helped cement her career, but it also reflects a broader pattern: Hollywood often celebrates the pain involved in telling a painful story, rather than building safer ways to tell it.

Great acting shouldn’t require being broken by the material.

13. Daniel Day-Lewis — My Left Foot (1989)

Method acting has a whole mythology, and Day-Lewis is one of the names most people bring up when they talk about total immersion.

For My Left Foot, he portrayed Christy Brown, a writer and painter with cerebral palsy, and he reportedly stayed in character for extended stretches, including using a wheelchair and relying on the crew for assistance as part of the performance.

That level of commitment helped shape the film’s authenticity, because the physical restrictions became real rather than mimed, and the acting feels startlingly embodied.

The problem is that this approach can create a situation where other people have to accommodate an actor’s “process” in ways that go beyond normal production demands.

It also raises ethical questions about what realism means when it affects everyone else’s working conditions.

Day-Lewis delivered a brilliant performance, but the larger conversation is whether intense immersion should be seen as the gold standard, or just one extreme path that not everyone should replicate.

If your process becomes a burden on the set, it stops being private preparation and becomes a shared consequence.

14. Shia LaBeouf — Fury (2014)

Some actors become known not just for commitment, but for escalating it into headline-making behavior, and LaBeouf’s reputation on Fury fits that pattern.

Reports and interviews around the film described him taking immersion very seriously, including adopting a rougher lifestyle on set and making choices that sounded more like endurance theater than acting preparation.

Some accounts even claimed he went as far as physically harming himself, which has circulated as part of the film’s behind-the-scenes lore, though the details often vary depending on who’s telling the story.

That inconsistency is exactly why the “too far” label applies, because when commitment becomes a spectacle, it can distract from the work and create an unsafe precedent.

The film itself is gritty, and his performance matches that energy, but it’s worth asking whether the same intensity could have been achieved through craft instead of extremes.

Acting is supposed to be controlled transformation, not chaos that risks real injury or destabilizes a production.

When the process becomes the story, the role starts to feel secondary, and that’s rarely a good sign.

Comments

Loading…