14 “Nice Guy” Characters Who Were Actually the Villain

The “nice guy” routine is one of storytelling’s sneakiest traps because it looks like safety, loyalty, and good intentions wrapped in a friendly smile.

These characters often show up as protectors, mentors, or romantic options, which makes their betrayal hit harder when the mask slips.

Sometimes they’re full-on villains hiding behind manners, and other times they’re the type of person who weaponizes decency to control the narrative.

Watching them charm everyone else while quietly tightening the screws can feel uncomfortably familiar, especially when the story treats their behavior as “romantic.”

Here are 15 “nice guy” characters who seemed lovable or harmless at first, but turned out to be the real danger.

1. Gaston — Beauty and the Beast

The village’s golden boy sells himself as a protector, but his confidence is really just entitlement with a smile.

He performs kindness like it’s a job interview, complimenting people only when it helps him stay adored and obeyed.

When Belle doesn’t play her assigned role, his “good guy” act curdles into humiliation, pressure, and public manipulation.

He frames the Beast as the monster to distract everyone from how aggressively he refuses to respect a woman’s choice.

Even his friendship is transactional, since loyalty is demanded, not earned, and dissent gets mocked into silence.

By the time the mob forms, it’s clear his true villainy was never fangs or claws, but control disguised as charm.

2. Prince Hans — Frozen

A polished smile and perfect manners make him look like the dream option, especially next to a reckless royal.

He mirrors what Anna wants to hear, using attentive listening as bait rather than genuine emotional connection.

The courtship moves fast because speed is part of the trick, giving her no time to notice the seams.

Once he has access to the throne, affection becomes a switch he flips off without a hint of regret.

His calmness in the betrayal scene is chilling, because it shows the “sweet” version was always a performance.

In the end, the villain twist works because he embodies the danger of mistaking charm and agreement for character.

3. Lotso — Toy Story 3

A soft voice and a welcoming hug make the daycare seem like a second chance for abandoned toys.

He builds trust by talking about pain, then uses that shared vulnerability to demand obedience from everyone around him.

The “for your own good” speeches sound reasonable until you realize they’re just rules meant to keep him in power.

He punishes dissent through rigid control, turning the sunny setting into a prison with a smiley-face logo.

Even when a path to redemption appears, he chooses revenge, because cruelty feels safer than accountability.

That contrast is what makes him terrifying, since the warm grandpa vibe is exactly how he gets people to surrender.

4. Mother Gothel — Tangled

A doting caretaker persona makes her feel like the only safe adult in the room, especially to someone raised in isolation.

She cloaks control in concern, insisting the outside world is dangerous while positioning herself as the sole source of love.

Her compliments are conditional and her criticism is constant, which trains Rapunzel to doubt her own instincts.

The guilt trips land like emotional shackles, because they make independence feel like betrayal rather than growth.

Even the playful teasing is sharp-edged, serving as a reminder that affection can be withdrawn at any moment.

By the end, the villain reveal isn’t a sudden twist, because every “loving” moment was really about ownership.

5. Judge Claude Frollo — The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Respectability and religious authority make him appear principled, which is exactly why his cruelty hides in plain sight.

He speaks in the language of morality while using power to punish anyone who threatens his control or desires.

His obsession gets reframed as “temptation,” letting him blame others for what he refuses to confront in himself.

The calm, measured delivery of his threats makes them worse, because violence feels justified when it wears holy robes.

He treats Quasimodo as both a possession and a sin, keeping him dependent through shame and isolation.

What exposes him as the real monster is not passion, but the cold certainty that his status entitles him to ruin lives.

6. Syndrome (Buddy Pine) — The Incredibles

A rejected sidekick story sounds sympathetic at first, because it begins with eagerness and admiration rather than malice.

He frames himself as a helpful fan, but the “support” is really a demand to be validated and elevated.

When he doesn’t get the recognition he feels owed, that wounded pride mutates into a revenge mission with a glossy brand.

He offers the world technology and progress, yet it’s built on manufacturing threats so he can sell solutions.

Even his “everyone can be special” line is a manipulation, because it’s less about equality and more about revenge on heroes.

The villainy lands because his niceness was always conditional, disappearing the moment admiration wasn’t guaranteed.

7. Gilderoy Lockhart — Harry Potter

Celebrity warmth and dazzling confidence make him look like the fun teacher who will finally make school exciting.

He flatters students and performs heroism, but everything is built on stolen stories and carefully edited lies.

His “helpfulness” is reckless because protecting his image matters more than keeping children safe in dangerous situations.

When confronted with reality, he chooses memory erasure over responsibility, showing how fragile the charm truly is.

He’s not evil in a grand, world-ending way, yet the selfishness leaves a trail of victims who never got credit or closure.

The scariest part is how easily people believe him, because we often confuse charisma with competence and attention with care.

8. President Snow — The Hunger Games

Polished manners and soft-spoken conversation make him feel like a reasonable statesman rather than a tyrant.

He projects calm authority, which lets him threaten people without raising his voice or giving them an obvious villain to fight.

The elegance is strategic, because it distracts from the brutal machinery he maintains through fear, spectacle, and scarcity.

Even his “advice” to Katniss is coated in civility, as if he’s doing her a favor by outlining the rules of survival.

He treats lives as chess pieces and calls it stability, which is a particularly insidious kind of villain logic.

By the time you see the full system, it’s clear the charm isn’t character, but a weapon that makes cruelty look inevitable.

9. Littlefinger (Petyr Baelish) — Game of Thrones

Friendly counsel and seeming loyalty make him look like the rare ally who understands how to survive a brutal court.

He speaks in helpful truths, but those truths are always angled to push people toward choices that benefit him.

By acting like a humble outsider, he gets underestimated, which gives him room to manipulate without immediate suspicion.

His kindness often arrives with a hidden invoice, because every favor is leverage for a future betrayal.

He fuels chaos while pretending to warn against it, then profits when others scramble to clean up the mess.

The “nice” mask works because it’s made of plausible deniability, leaving everyone feeling foolish for trusting him too late.

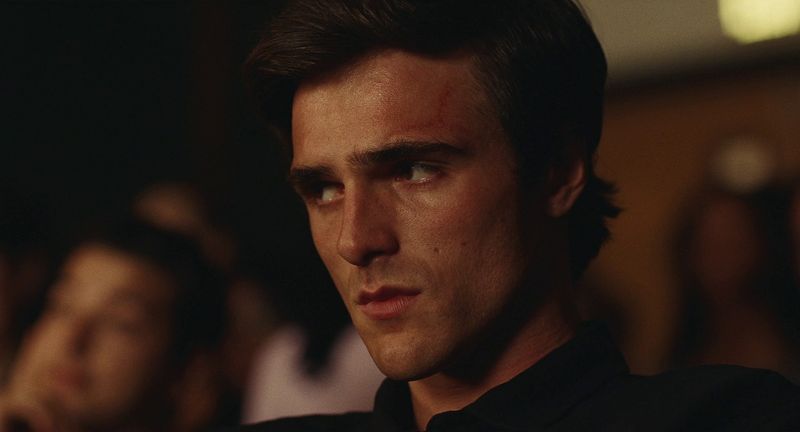

10. Nate Jacobs — Euphoria

A clean-cut image and surface-level politeness can make him look like the kind of boyfriend parents would approve of.

He uses calm conversations and carefully chosen apologies to reset the narrative whenever his behavior starts to expose him.

Underneath the charm sits a need for control, which shows up in intimidation, surveillance, and emotional pressure.

He weaponizes vulnerability by learning what people fear, then pressing on those bruises until they comply.

The scariest moments are the quiet ones, because the threat lives in what he could do rather than what he’s openly saying.

That contrast is why he fits the “nice guy” villain mold, since the public persona is exactly how he hides the private danger.

11. Joe Goldberg — You

A soft voice and bookish sweetness make him seem like the rare man who truly listens and sees you.

He narrates his obsession as devotion, turning boundary-crossing behavior into a love story he expects you to applaud.

The gestures feel thoughtful until you realize they are surveillance, because he gathers information to control outcomes.

He justifies harm as protection, which is how he transforms violence into something he can call “necessary.”

Each relationship becomes a mirror for his ego, and the moment a woman becomes real and complicated, he punishes her humanity.

The villain twist isn’t that he’s capable of cruelty, but that he believes he’s the hero even while destroying lives.

12. Gale Hawthorne — The Hunger Games

A loyal best friend role makes him feel like the safe choice, especially next to a world filled with predators.

He starts as someone who shares hardship and speaks openly about injustice, which builds trust through shared anger.

Over time, that anger hardens into certainty, and certainty becomes permission to treat people as acceptable collateral.

He frames ruthless tactics as necessary for freedom, but the logic grows colder as the body count becomes abstract.

Even when love is in the mix, he sometimes treats Katniss like a symbol instead of a person with limits.

The villain-adjacent shift is painful because it shows how “good intentions” can become dangerous when empathy is sacrificed for victory.

13. Cal Hockley — Titanic

Wealth, manners, and protective gestures make him look like the stable fiancé who can offer safety in a chaotic world.

He performs generosity in public, but the private version is controlling, suspicious, and deeply entitled to obedience.

His “care” is really possession, which shows up in the way he speaks about Rose as if she’s part of his status.

When she resists, he escalates fast, using threats and manipulation to corner her into compliance.

Even the romantic trappings feel strategic, because grand gifts and polished appearances are meant to silence questions about his behavior.

He becomes the villain not because he lacks charm, but because his charm is the wrapper around coercion.

14. Arthur Fleck — Joker

A fragile, overlooked man can initially read as harmless, especially when the world seems determined to humiliate him.

He earns sympathy through vulnerability, but the story shows how quickly that sympathy can turn into excuse-making for harm.

As rejection piles up, he starts rewriting reality so that violence feels like a justified response to being ignored.

The “nice” exterior becomes a mask for resentment, and resentment becomes a worldview where other people are props.

His most chilling moments are when he looks calm, because it signals he has stopped seeing others as human.

The villainy here is complicated, yet it still warns how dangerous it is to romanticize suffering when it becomes permission to destroy.

Comments

Loading…