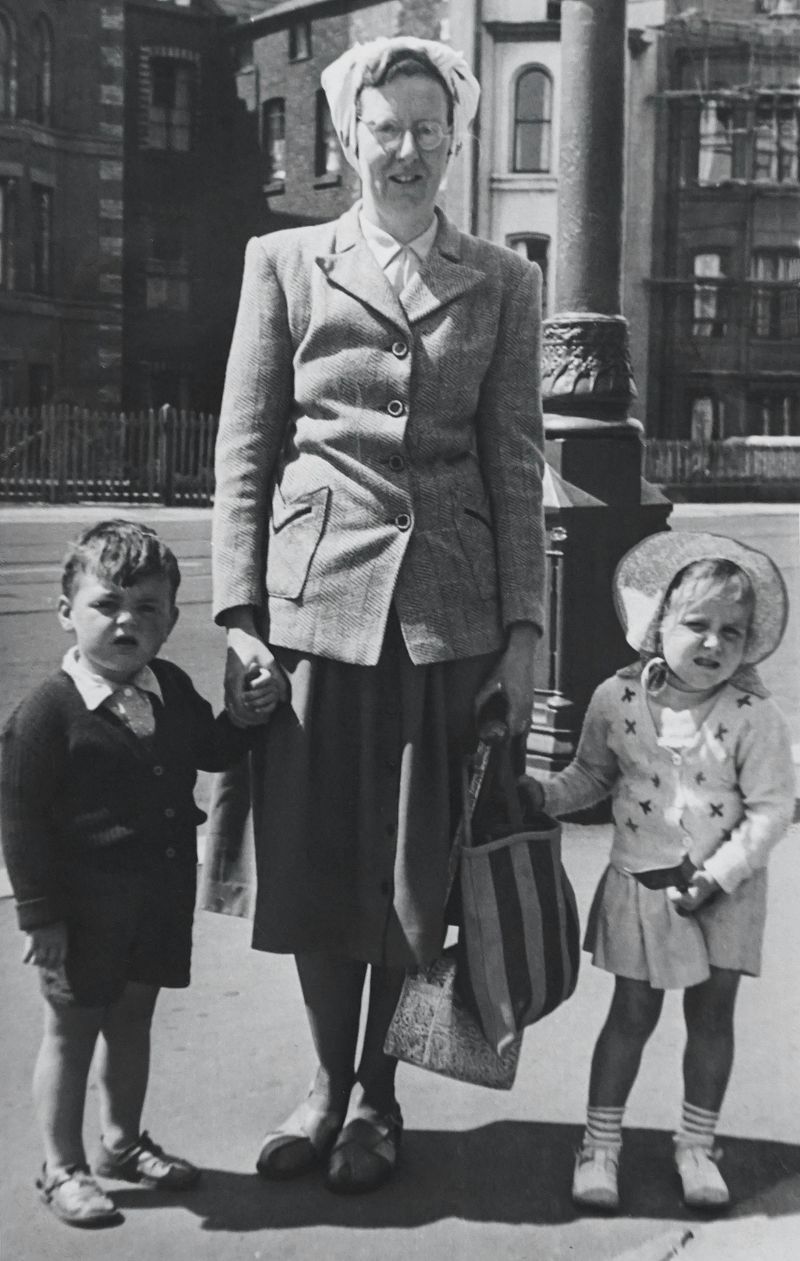

25 Things Grandmothers in the ’50s Believed About Raising Kids

Parenting in the 1950s looked vastly different from how we raise kids today. In an era shaped by post-war ideals, traditional family structures, and strict societal norms, grandmothers developed a set of beliefs and practices that defined child-rearing for a generation. These weren’t just personal preferences—they were widely accepted “truths” passed down through communities, reinforced by neighbors, doctors, and popular media alike.

1. Children Should Be Seen and Not Heard

Expressing opinions or emotions in front of adults was often considered impolite. Many grandmothers believed that well-behaved children stayed quiet in adult settings, listened intently, and spoke only when spoken to. Chatter, backtalk, or even excitement could be seen as disruptive or disrespectful.

This belief reflected the era’s broader focus on obedience and conformity. A quiet child was assumed to be a good child—calm, respectful, and properly disciplined. Encouraging kids to speak up or question authority was rarely part of the parenting playbook.

For many families, the dinner table or family gatherings were silent affairs, with children learning from observation, not conversation.

2. Spanking Is an Effective Discipline Tool

Back in the ’50s, spanking wasn’t just accepted—it was expected. Grandmothers often believed that a swift swat on the bottom was the fastest way to correct bad behavior and teach respect. It wasn’t seen as harmful, but rather as a natural part of discipline.

Physical punishment was rarely questioned, and parents who didn’t use it were sometimes viewed as too lenient. The idea was that pain would leave a lasting lesson, especially when paired with stern words and a “because I said so” attitude.

Today, research has shifted perspectives, but back then, spanking was considered both loving and necessary.

3. Mothers Belong at Home With the Children

For many grandmothers, a good mother stayed home. Raising kids was viewed as the woman’s full-time role, and working outside the home was often associated with neglect or financial desperation. This belief was deeply tied to post-war ideals of domestic life.

Women were expected to cook, clean, and care for the children while their husbands provided. Those who chose to pursue careers were sometimes judged harshly by their peers and elders alike.

The notion of maternal sacrifice was glorified—being present for every moment, from diaper changes to school pickups, was not just encouraged; it was morally expected.

4. Fathers Shouldn’t Be Too Involved in Childcare

Men who changed diapers or rocked a baby to sleep were the exception, not the rule. Many grandmothers saw active fatherhood as unnecessary or even emasculating. Fathers were the breadwinners, not the babysitters.

Traditional roles were sharply divided. Mothers handled the emotional and physical demands of parenting, while dads focused on discipline and finances. A dad’s presence was often limited to teaching lessons, enforcing rules, or attending important milestones.

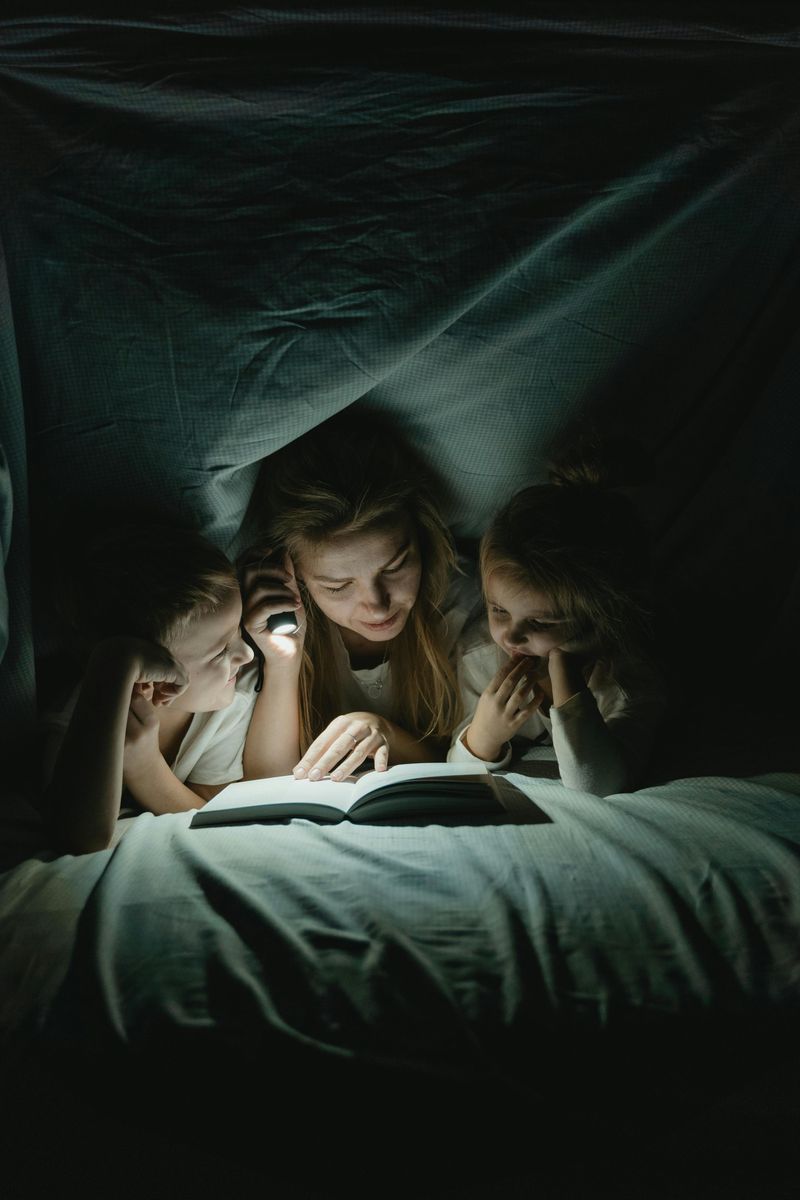

This division wasn’t questioned much—it was just how things were done. A father’s love was shown through work ethic and providing, not through bedtime stories or bath time.

5. Crying It Out Builds Character

Comforting a crying baby too quickly was thought to spoil them. Grandmothers in the ’50s believed that allowing children to cry it out helped them develop emotional toughness and independence. Picking them up too often was seen as a sign of weakness—for both the parent and the child.

Babies were frequently left alone to settle themselves, even if their cries lasted for long periods. This approach was often backed by pediatric advice of the time, which emphasized discipline over nurturing.

Soothing a child was considered indulgent. Tough love, even from the crib, was considered a necessary part of growing up.

6. Formula Is Just as Good—If Not Better—Than Breastmilk

Many grandmothers trusted formula over breastfeeding. Science and advertising convinced parents that modern baby formulas were just as nutritious—and more convenient—than nursing. Breastfeeding was sometimes even seen as outdated or only for mothers who couldn’t afford formula.

Doctors often recommended formula feeding, citing measured nutrients and predictability. Grandmothers believed it made babies grow faster and sleep longer, which only reinforced the idea that it was superior.

Social stigma also played a role. Nursing in public or even at home in front of others was often frowned upon, making formula a preferred and “polished” alternative for modern mothers.

7. TV Won’t Hurt—Just Don’t Sit Too Close

Television became a central part of family life in the 1950s, and many grandmothers embraced it as both entertainment and education. While too much screen time wasn’t yet a concern, they did warn kids not to sit too close or their eyes might go “square.”

TV was seen as a harmless way to keep children quiet and occupied. Cartoons, westerns, and family sitcoms gave parents a break while kids sat mesmerized for hours.

Despite minor concerns about eyesight, there was little awareness of the long-term effects of screen exposure. To them, TV was a miracle of modern parenting convenience.

8. Cod Liver Oil Is a Must

Lining up for a spoonful of cod liver oil was a daily ritual for many kids raised in the ’50s. Grandmothers swore by it as a cure-all—believing it would build strong bones, prevent colds, and promote general good health.

The taste was awful, but refusal wasn’t tolerated. Many believed that its health benefits far outweighed a few seconds of gagging. Doctors often endorsed it, reinforcing its status as a household staple.

Vitamin supplements weren’t as common back then, so cod liver oil filled that nutritional gap. In their eyes, a healthy child was an oily-mouthed, well-behaved one.

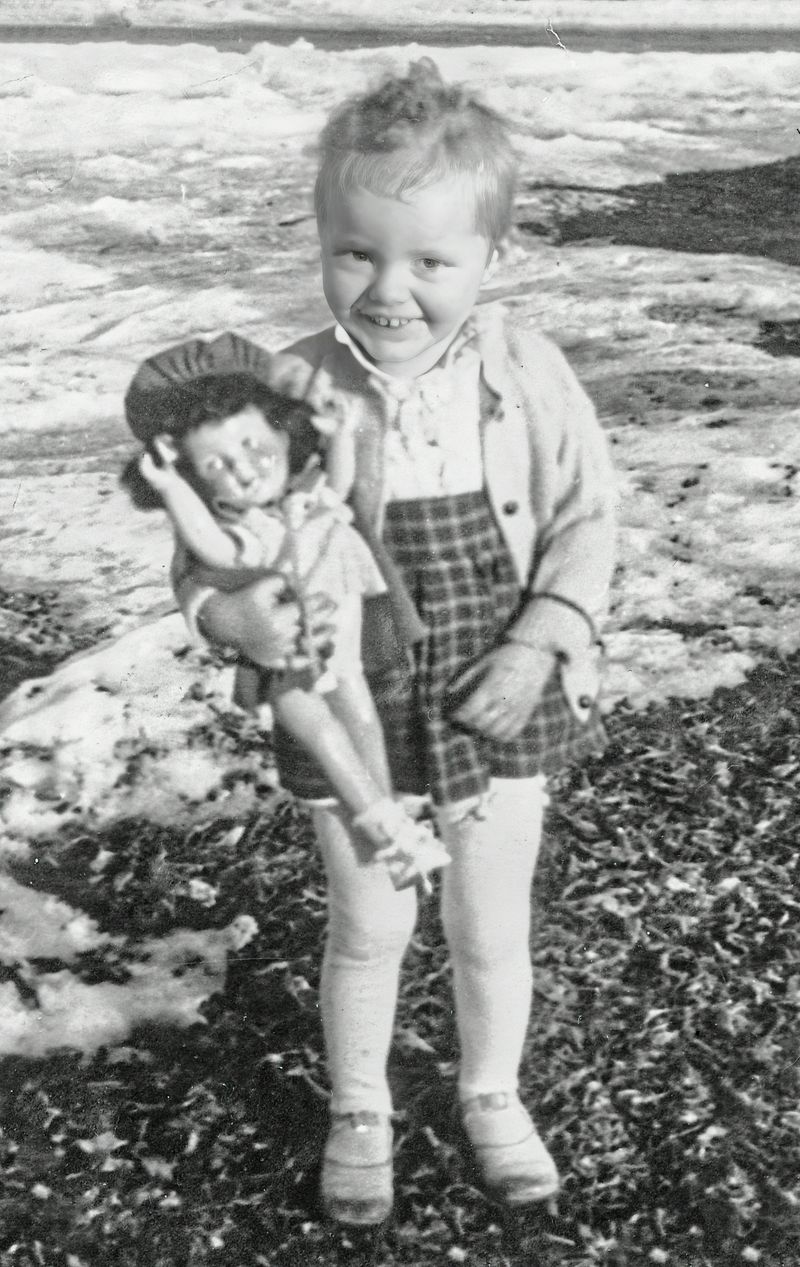

9. Kids Should Always Be Neat and Presentable

Sloppy appearance reflected poorly on the parents, or so many grandmothers believed. Children were expected to be clean, neatly dressed, and tidy—especially in public. Dirty fingernails or wrinkled clothes were a sign of laziness or neglect.

Sunday best wasn’t just for church. Ironed shirts, polished shoes, and well-groomed hair were everyday expectations in many households. Even play clothes had to look somewhat presentable.

This emphasis wasn’t about vanity—it was about teaching discipline, pride, and self-respect. A child who looked put together was assumed to be better behaved and better raised, regardless of what was going on inside.

10. Children Must Address Adults as “Sir” or “Ma’am”

Respect was non-negotiable in the 1950s. Grandmothers insisted that children use formal titles when speaking to adults—“Yes, ma’am,” and “No, sir,” were expected responses, and anything less could be considered rude or even rebellious.

This practice wasn’t just about politeness; it was about enforcing authority. Adults were to be respected without question, and language was one of the primary tools for maintaining that social order.

Using first names for adults was rare and often discouraged. Even teachers and neighbors were addressed with titles, creating clear boundaries between generations and emphasizing a culture of deference.

11. Sleeping on the Stomach Is Safest for Babies

Today’s “Back to Sleep” campaigns directly contradict what many grandmothers were taught. In the ’50s, stomach sleeping was believed to reduce choking risks and help babies sleep more soundly.

This advice came straight from pediatricians of the era, so it was rarely questioned. Mothers were encouraged to lay babies down on their tummies, often surrounded by pillows and blankets—a far cry from today’s minimalistic, safety-first sleep environments.

While the intentions were good, we now know this practice increases the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Still, grandmothers followed what they thought was the safest method at the time.

12. Only Mothers Know Best—Forget the Doctor

Medical advice wasn’t always the go-to in child-rearing decisions. Many grandmothers trusted their instincts—or their own mothers’ advice—over what a doctor had to say. If something worked for their kids, they saw no reason to change course for the next generation.

Home remedies and folk wisdom often took precedence. Whether it was curing a fever with vinegar socks or soothing a cough with honey and lemon, grandmothers took pride in their “tried and true” methods.

Doctors were respected, of course—but when it came to babies, many believed a mother’s gut was more reliable than a stethoscope.

13. School Is Where You Learn Everything Important

The idea that education belonged strictly in the classroom was a common belief. Many grandmothers didn’t feel the need to supplement learning at home unless it involved memorizing multiplication tables or doing homework.

Children were sent to school to be molded, taught, and disciplined by professionals. Parents focused on behavior and chores, not nurturing creativity or emotional development through learning at home.

There was little emphasis on things like emotional intelligence or critical thinking outside of academics. Learning was structured and hierarchical—books, teachers, and grades ruled the day, and that was considered more than enough.

14. Vaccines Are Optional, Not Essential

Although vaccines were becoming more common in the 1950s, some grandmothers remained skeptical. Rumors and misinformation about side effects made many hesitant, especially in smaller towns or rural communities.

Trust in modern medicine was growing, but not universal. Some families delayed or even skipped shots entirely, believing natural immunity or “getting through it” was just part of childhood.

Polio campaigns started changing public opinion, but vaccine hesitancy still lingered. Grandmothers who hadn’t seen certain diseases firsthand often questioned whether the risk of vaccination outweighed the illness it was supposed to prevent.

15. Sugar Keeps Kids Happy—And That’s What Matters

Sweet treats were not just common—they were rewards, comforts, and bribes rolled into one. Many grandmothers didn’t worry about sugar content. If it put a smile on a child’s face, it was worth it.

Cakes, cookies, pies, and sugary cereals were staples in the 1950s pantry. Dental care was important, sure, but cavities weren’t enough reason to cut back on dessert.

There was little concern about hyperactivity or long-term health effects. Sugar was just a part of childhood, and limiting it too much was seen as unnecessarily strict—even mean.

16. Routines Must Be Strictly Followed

A consistent schedule was seen as a hallmark of good parenting. Grandmothers believed that children thrived when their days were predictable—wake up at 7, lunch at 12, bed by 8. No exceptions.

Mealtimes, naptimes, and even playtime were carefully structured. Any deviation was viewed as chaotic or irresponsible parenting. Spontaneity wasn’t encouraged—it disrupted the flow of the day.

This rigid approach was about more than just convenience. It was believed to teach discipline, respect for authority, and time management skills—even to toddlers. A tightly run household was a source of pride and order.

17. Girls Should Help in the Kitchen; Boys in the Yard

Household roles were clearly defined, and grandmothers in the ’50s passed those expectations down early. Daughters were taught to cook, clean, and care for younger siblings. Sons, on the other hand, were expected to mow lawns, take out the trash, or help with repairs.

These weren’t just chores—they were preparation for their “future roles.” Girls learned how to be homemakers, while boys were groomed to become providers and protectors.

Crossing these gender lines wasn’t encouraged. A boy who enjoyed baking or a girl who liked tools might be gently redirected—or openly scolded. Gender norms were rarely challenged.

18. Hand-Me-Downs Build Character

Wearing older siblings’ clothes wasn’t something to be ashamed of—it was the norm. Grandmothers believed hand-me-downs taught gratitude, humility, and resourcefulness. If it was still in good shape, you wore it—period.

Frugality was a virtue in post-war households. Stretching the family budget meant reusing clothes, toys, and sometimes even school supplies. Children learned not to expect brand-new items with every growth spurt.

Complaining about hand-me-downs was often met with a lecture about “kids these days” or a reminder that someone else had it even harder. Appreciation for what you had was a non-negotiable family value.

19. Dirt Won’t Hurt—It Might Even Help

Getting messy was part of growing up. Grandmothers encouraged kids to play in the yard, dig in the dirt, and climb trees—sometimes barefoot. Germs weren’t feared the way they are today.

A scraped knee or muddy hands were seen as signs of a good day, not something to panic over. In fact, many believed that exposure to the outdoors helped “toughen up” kids and build natural immunity.

Over-sanitizing or coddling children was considered unnecessary. The world wasn’t seen as dangerous—it was a playground meant to be explored, even if it meant tracking mud through the kitchen.

20. Kids Don’t Need Privacy

Doors stayed open, journals got peeked at, and conversations were often overheard on purpose. Privacy wasn’t a high priority in 1950s households. Grandmothers believed that too much secrecy encouraged misbehavior.

Children were viewed as extensions of the household, not independent individuals. Bedrooms were for sleeping, not for “alone time.” Asking for privacy was sometimes seen as suspicious or even disrespectful.

Parents kept a close eye on their kids’ actions, friends, and habits. It wasn’t about invading their space—it was about maintaining control and preventing trouble before it started. Trust was earned slowly, and usually with age.

21. Punishment Should Fit the Crime—And Be Immediate

Discipline wasn’t delayed or sugarcoated. When kids misbehaved, consequences followed swiftly and clearly. Grandmothers believed that immediate punishment reinforced the lesson better than a delayed or drawn-out response.

This approach was rooted in the idea that children needed to connect action and consequence quickly. Whether it was losing dessert, being grounded, or receiving a spanking, there was little room for negotiation.

Parents didn’t worry about explaining every detail or validating feelings. The focus was on correction, not conversation. The faster the punishment was handed out, the more effective it was thought to be.

22. It’s Rude to Question Your Parents

Challenging authority wasn’t just frowned upon—it was seen as a direct act of disrespect. Grandmothers in the ’50s believed that a child’s job was to listen, obey, and not question adult decisions.

Phrases like “because I said so” weren’t meant to be conversation enders—they were the rule of law. Asking “why” was sometimes seen as backtalk or a sign of defiance, rather than curiosity.

This approach was rooted in hierarchy. Adults were to be respected automatically, not earned through mutual understanding. Questioning a parent’s logic was rarely tolerated and often swiftly corrected.

23. You Can Never Say “Thank You” Too Much

Good manners were essential to being well-raised. Grandmothers emphasized constant gratitude—children were expected to say “please” and “thank you” for everything, no matter how small.

It wasn’t just about politeness; it was about humility and respect. A thankful child was seen as thoughtful, appreciative, and civilized. Forgetting to express gratitude could result in a lecture—or worse, a withheld treat.

These courtesies weren’t just used at home. Saying “thank you” to neighbors, teachers, and even strangers was seen as a reflection of one’s upbringing. Gratitude was a sign of good character, and it started early.

24. Talking About Feelings Is a Waste of Time

Emotional expression was often misunderstood. Grandmothers believed that focusing too much on feelings would make kids weak, overly sensitive, or self-indulgent. Boys in particular were taught to “toughen up” and “quit crying.”

Emotional restraint was a virtue. Problems were solved through action—not conversation. If you were sad, you were told to get busy. If you were angry, you were told to calm down and move on.

Therapy and open emotional dialogue were rare, if not stigmatized. Feelings were considered private, and sometimes even shameful. Strength meant composure, not vulnerability.

25. Raising Tough Kids Is More Important Than Raising Happy Ones

Happiness wasn’t always the end goal. Grandmothers prioritized resilience, self-reliance, and discipline over emotional well-being. Life was hard, and children needed to be prepared for that reality—not coddled through it.

Smiles were great, but grit mattered more. Kids who complained too much or needed constant encouragement were seen as ill-equipped for adulthood. Strength, not joy, was considered the real mark of a successful upbringing.

This mindset stemmed from survival. Many grandmothers had lived through war, poverty, or economic instability. To them, a tough child would endure. A happy one might crumble when life got real.

Comments

Loading…